Translating deep thinking into common sense

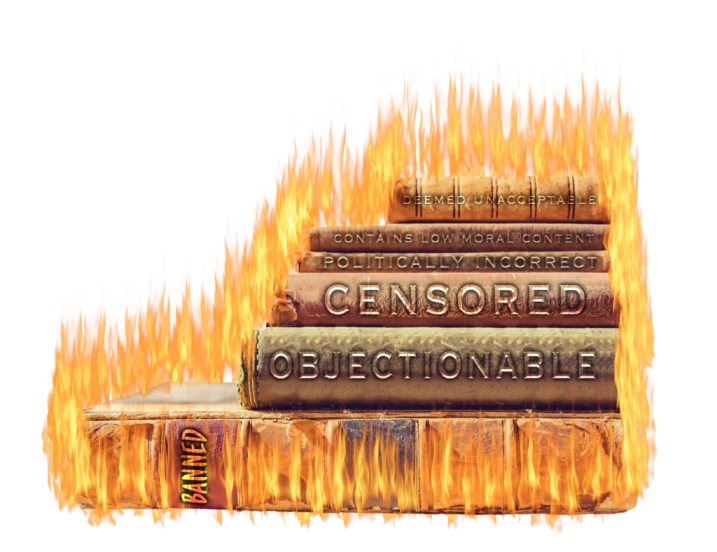

Disagreement with the Left is the New Blasphemy

By Walter Donway

October 10, 2018

SUBSCRIBE TO SAVVY STREET (It's Free)

To: The Political Correctness Thought Police

From: John Stuart Mill

Subject: On Liberty

This is Memo II of the three-part series. Memo I was “A Memo to the Thought Police on Liberty.”

The Utility of Allowing Disagreement

This (see Memo I) is not our only philosophical inheritance on the nature of liberty. What about those who came before Mill—John Milton in the Areopagitica (published 1644) and John Locke in his works on natural rights to life, liberty, and property (in the mid-17th Century)? But Milton excluded toleration of differences that might subvert religious or civil authority, opinion “impious or evil” against religion or manners. And Locke argued that denial of the existence of God could not be legally tolerated because what would guarantee “promises, covenants, and oaths”?

In Mill’s time, people still were sentenced to prison for refusing to take an oath in court. And Mill could attend neither Oxford nor Cambridge University because he would not swear to the 39 articles of the Church of England.

Having stated his “single principle” for preserving liberty, Mill said he would defend that principle not on the grounds of “the idea of abstract right as a thing independent of utility. I regard utility as the ultimate appeal of all ethical questions.”

The individual is defined, above all, by exercise of reason and judgment. To leave his judgment free to operate—in reaching conclusions and acting upon them, either as advocate or in conducting his affairs—is the full meaning and significance of liberty.

That statement has troubled scholars and a great many defenders of liberty. Many do not wish to defend liberty as merely practical. And scholars did not see how the arguments Mill makes are utilitarian. Professor Himmelfarb agreed with them. Mill’s arguments, she showed, make liberty an end in itself because it is the key to the nature of the individual. The individual is defined, above all, by exercise of reason and judgment. To leave his judgment free to operate—in reaching conclusions and acting upon them, either as advocate or in conducting his affairs—is the full meaning and significance of liberty.

All of Mill’s arguments for respecting the liberty of the individual, all the “utility” of doing so (Mill rarely uses the term), is that individual happiness depends upon it. As does any possible contribution of the individual to society, to the happiness of other individuals.

Why, then, did Mill invoke the method of utilitarianism? The answer is the story of Mill’s life, which is told in his famous Autobiography. He was raised, and educated (entirely privately, he never attended school), by the two greatest philosophers of Utilitarianism: his father, James Mill, and his father’s own mentor and colleague, Jeremy Bentham. They had no plan for the young man’s life, no wish for his future, but that he become the perfect exemplar and advocate of the Utilitarian calculus of pleasure and pain, the famous ethical standard of “the greatest good for the greatest number.”

In two crises of near-suicidal depression, rage, and intellectual rebellion, the first when he was only 20, Mill broke out of the prison of Utilitarianism—and his own carefully engineered destiny. He never openly rebelled against Bentham and his father, but upon his father’s death experienced a profound sense of liberation. Indeed, said Himmelfarb, he wrote On Liberty, in the closest collaboration with his wife (that is another remarkable story), and wrote it against Utilitarianism, and, especially, the formulations of Bentham.

“In the utilitarian scheme,” wrote Himmelfarb, “it was precisely the function of the legislator to do that which would make individuals, singly and collectively, happier—which is why Bentham himself had utter contempt for the idea of liberty.”

She writes: “What we are left with, then, is what John Stuart Mill, more than anyone else, bequeathed to us: the idea of the free and sovereign individual.” Precisely because Mill espoused “a single principle”—and intended it as unqualified, absolute.

He wrote “it will be desirable to fix down the discussion to a concrete case: and I choose, by preference, the cases which are least favorable to me. … Let the opinion impugned be the belief in God and a future state, or any of the commonly received doctrines of [religious] morality.”

If we do so, today, however, we have let Mill down. Undoubtedly, there are communities, even parts of America, where arguments for atheism meet with social condemnation, even ostracism. But nowhere, on any level of government, is any proposal to enforce religious belief. And there is no intellectual community of much significance where atheism, a secular viewpoint and morality, are reviled. There are no thought vigilantes watching for unbelievers and no one would cite a secular worldview as an offense against political correctness.

In honor of Mill, let me put forward as “cases least favorable” to tolerance in the name of liberty, some certifiably politically incorrect ideas. These are not my views. In fact, they are so politically incorrect that it is dangerous even to state them in print. I will label each one a “politically incorrect proposition.”

If disavowal of “belief in God and a future state” are what we are pretending to champion in the name of liberty, then our game is a slam dunk. In honor of Mill, let me put forward as “cases least favorable” to tolerance in the name of liberty, some certifiably politically incorrect ideas. These are not my views. In fact, they are so politically incorrect that it is dangerous even to state them in print. I will label each one a “politically incorrect proposition.”

Politically incorrect proposition #1: Although this says nothing about any particular individual, the science of measuring innate general intelligence (“G”) consistently supports the conclusion that the races differ significantly in their average IQ.

Politically incorrect proposition #2; Equal pay for women as a government policy is an unwarranted interference in the free market as well as an example of collectivist groupthink.

Politically incorrect proposition #3: ‘Rainbow’ diversity is virtually meaningless because it is viewing people as members of racial and ethnic collectives; the only genuine diversity is among individual minds and ideas.

Politically incorrect proposition #4: Health care obviously cannot be a “right” because implementing it requires violating the legitimate right to property of those forced to pay for it.

Politically incorrect proposition #5: America is the morally greatest nation on earth based upon its founding principles of human rights, strictly limited constitutional government, individualism, and capitalism—ideals upheld and reaffirmed in a great civil war.

Politically correct proposition #6: Israel’s right to its entire territory rests firmly on its half-century record of upholding human rights, the rule of law, and the free market more consistently than any other nation in the Middle East.

Selected more or less at random, and I hope formulated fairly to their advocates (whoever they may be), these half a dozen ideas, with perhaps a few exceptions geographic or institutional, are political anathema in America, today. They are the secular equivalent of atheism in Mill’s day.

Don’t bother to propose to advance them in any mainstream media except for eliciting unequivocal condemnation. Don’t accept an invitation to present and discuss some of them on a college campus—you will meet with violent protest. Do not advocate any of them in a political campaign—your next stop will be met by violent demonstrators. Do not raise any of them for discussion in class—you will be disciplined. Don’t post most of them on Facebook—you will tick off the “hate speech” algorithm. And don’t try to discuss them at a cocktail party—you will never, ever, be invited back.

Do not commit blasphemy.

Most of Mill’s arguments will sound familiar. That is, if you conceive them as applying to government censorship or other repression of ideas. He applied these arguments as well, however, to reception of politically incorrect options on the social level. Of course, he did not propose resorting to the law to suppress the active condemnation of opinions viewed as obnoxious or the ostracism of those holding such opinions. His appeal was to the conscience—and the self-interest—of individuals and society.

“The peculiar evil of silencing the expression of an opinion is that it is robbing the human race, posterity as well as the existing generation—those who dissent from the opinion still more than those who hold it. If the opinion is right, then we are deprived of the opportunity of exchanging error for truth; if wrong, they lose, what is almost as great a benefit, the clearer perception and livelier impression of truth produced by its collision with error.”

He begins with familiar arguments: “The peculiar evil of silencing the expression of an opinion is that it is robbing the human race, posterity as well as the existing generation—those who dissent from the opinion still more than those who hold it. If the opinion is right, then we are deprived of the opportunity of exchanging error for truth; if wrong, they lose, what is almost as great a benefit, the clearer perception and livelier impression of truth produced by its collision with error.”

Sure, sure, we all agree with that. Mill elaborates:

“First, the opinion … may possibly be true. Those who desire to suppress it, of course, deny its truth; but they are not infallible. … All silencing of discussion is an assumption of infallibility.”

But “Unfortunately for the good sense of mankind, the fact of their infallibility is far from carrying the weight in their practical judgement which is always allowed to it in theory … few think it necessary to take any precautions against their own fallibility. …”

As long as a man’s particular “collective authority” supports him, he is not shaken “by his being aware that other ages, countries, sects, churches, classes, and parties have thought, and even now think, the exact reverse.”

Yeah, yeah, but, “one might object,” writes Mill, “that there is no greater assumption of fallibility in forbidding the propagation of error than any other thing done by public authority.” Just because our judgment may be wrong, we can’t refrain from using judgment at all. Should we never act on our opinion because we may be wrong? We always have to assume our opinion to be true to guide our conduct. And we also assume our opinion is correct in suppressing obnoxious errors.

Mill responds. “There is the greatest difference in assuming an opinion to be true because, with every opportunity for contesting it, it has not been refuted, and assuming its truth for the purpose of not permitting its refutation.”

Why haven’t we gone even further astray than we have in conducting our lives according to our opinions, asks Mill, since “on any matter not self-evident there are ninety-nine persons totally incapable of judging of it for one who is capable …”?

“… the source of everything respectable in man either as an intellectual or as a moral being … [is] that his errors are corrigible. He is capable of rectifying his mistakes by discussion and experience. … The whole strength and value … of human judgement depending on the one property, that it can be set right when it is wrong.”

“… the source of everything respectable in man either as an intellectual or as a moral being … [is] that his errors are corrigible. He is capable of rectifying his mistakes by discussion and experience. … The whole strength and value … of human judgement depending on the one property, that it can be set right when it is wrong.”

That, and that alone, is the final basis of justifiable reliance on our opinion: that we have “sought for objections and difficulties instead of avoiding them … shut out no light which can be thrown on the subject from any quarter. …” Then, we have a right to think our judgment better than that of any person who has not done so.

All right, very inspiring. But even if we are not infallible in judging truth, are there not “certain beliefs so useful, not to say indispensable, to well-being that it is as much the duty of governments to uphold these beliefs as to protect any of the other interests of society”?

I am sure that the reader will have one or two of the politically incorrect propositions to bring forward in evidence. I know of famous individuals in the field of intelligence studies who have said that, yes, all the evidence appears to point to systematic average differences in the IQ among races, but it would do society more harm than good to openly discuss it.