Translating deep thinking into common sense

The Courage to Face a Lifetime: Nathaniel Branden, 1930-2014

By Joel Wade

December 6, 2014

SUBSCRIBE TO SAVVY STREET (It's Free)

I’ve lost a mentor and a dear friend; Nathaniel Branden passed away on Wednesday, Dec. 3rd. Playful, brilliant, mischievous, incisive, inspiring… He was the best ally a young soul striving for strength and self-possession could have.

When someone we care about passes, we long for stories that remind us of them; stories that help us feel like we can still know them better, as though they’re somehow still here, and we can continue to feel closer to them, if only for a little while longer; while we get used to the jarring truth that they’re gone.

There are stories that are public knowledge – and they are big stories. Nathaniel was instrumental in creating a systematic philosophy and organized school of thought from the novels and thought of Ayn Rand. She was his mentor… among other things. With his founding of the Nathaniel Branden Institute and the spread of Objectivism as a school of philosophy in the 1950’s and 60’s, he may be the man most responsible for the intellectual growth of the modern liberty movement.

After he and Rand split, he focused on his work with self-esteem. Earned self-esteem; which is different from self esteem as it has been researched and applied in policy. I would say that his view of self-esteem is closer to the title of one of my favorite of his books, “Honoring the Self,” than to the popular definition of self-esteem, which is simply, “feeling good about yourself.”

For Nathaniel, healthy self-esteem is not about just having happy feelings – and it’s definitely not something fragile, that can be given or taken away by others. It’s a deep internal sense of ownership; it’s about consciousness, responsibility, conscientiousness, self-discipline, self-awareness…. To do justice to his work, there will one day have to be some way to measure and study these qualities taken as a whole.

That’s a brief introduction to the man for those who may not know him or his work. What I have to say here is more personal.

I first met Nathaniel and his then wife Devers in 1980, at one of their weekend “Intensives.” I was a 20 year old college student, still searching for my path. Seeing the two of them work together was exhilarating. I was struck by Nathaniel’s brilliant and clear teaching, the playful and loving spirit between he and Devers, the moving work they did with the group, and the practical and expansive vision of what psychology could bring.

I had a profound personal moment of inspiration and clarity that weekend. The next day without hesitation, I changed my major to psychology. I knew what I wanted to do, and who I needed to learn from.

Over the years, Nathaniel was a consistently supportive, sometimes irritable, often impishly playful, always helpful mentor. He let me sit in on his groups, he took the time to discuss his thinking and strategy with me; and he encouraged me to study a wide range of thought and practice.

One day, as everyone sat waiting for a group to begin, Nathaniel popped his head in, casually leaned against the doorway, and with his familiar grin said, “You know, I’m getting tired of all this sentence completion business. How about we all go to the pool in the backyard, and I’ll just hold each of you under water until you promise to give up your problems?”

There were no takers, so he just shrugged, plunked himself in his chair, and said, “Okay, we’ll do it the usual way.” Of course he was having fun with this. But humor and playfulness in itself is a powerful intervention. Our troubles grow when we live too deeply inside them. The kind of mischief Nathaniel brought to his work served to pop people out of themselves, and forced them to come out and play. The world becomes bigger, more expansive, and our problems become smaller in comparison, when we play.

I asked him once, “What’s the most important thing you do with your clients?” He thought for a moment, and then he said, “I look for the best within them. I look for that part of them, even if they aren’t aware of it themselves. I speak to that part, and help them to bring it out.”

And he did that. Nathaniel looked for the best in people. Not in some kind of phony, sappy way, but seriously… playfully… relentlessly.

Sometime during the first couple of years I knew him I asked him for some “fatherly advice,” on dating. He looked at me with that warm smile of his, and said, simply, “Just, be friendly.” With all the stupid advice and supposed “rules for dating” that were circulating back then in the early 80’s, that simple statement cut through all the confusion and game playing, and brought it all back to what’s fundamental: It’s not complicated, just be present with who you’re with, be friendly, be yourself.

We know now from research that a sense of deep friendship and allegiance between partners is what’s most important in a relationship. I got that from Nathaniel in those three words, “Just, be friendly.”

I’ve known Nathaniel for 35 years, my entire adult life. I know I wouldn’t be the man I am today without his influence and friendship. More than anything, the gift that Nathaniel gave to me was a sense of moral confidence.

When I say moral confidence, I don’t mean the confidence to push my morality onto others. I mean the confidence to know deeply, with certainty, that my life matters, that my happiness matters, that love, joy, and happiness is what life is about. The corollary to that, of course, is a deep – I’d even say fierce – respect and honor for other people’s life, happiness, joy, and love. It makes it almost necessary to champion this in others.

It’s this quality, I think, that made his work so very important. If we’re going to change anything in our lives, it has to matter, it has to mean something. Nathaniel’s work wasn’t just about how to overcome psychological troubles; it was about nurturing an adventurous spirit, a heroic vision of life. This life matters, dammit! Dive in, embrace it! Use that spirit and momentum to drive through your problems to get to what’s really important.

Life is to be lived, embraced, savored. Even when things are hard; even when everything’s falling apart.

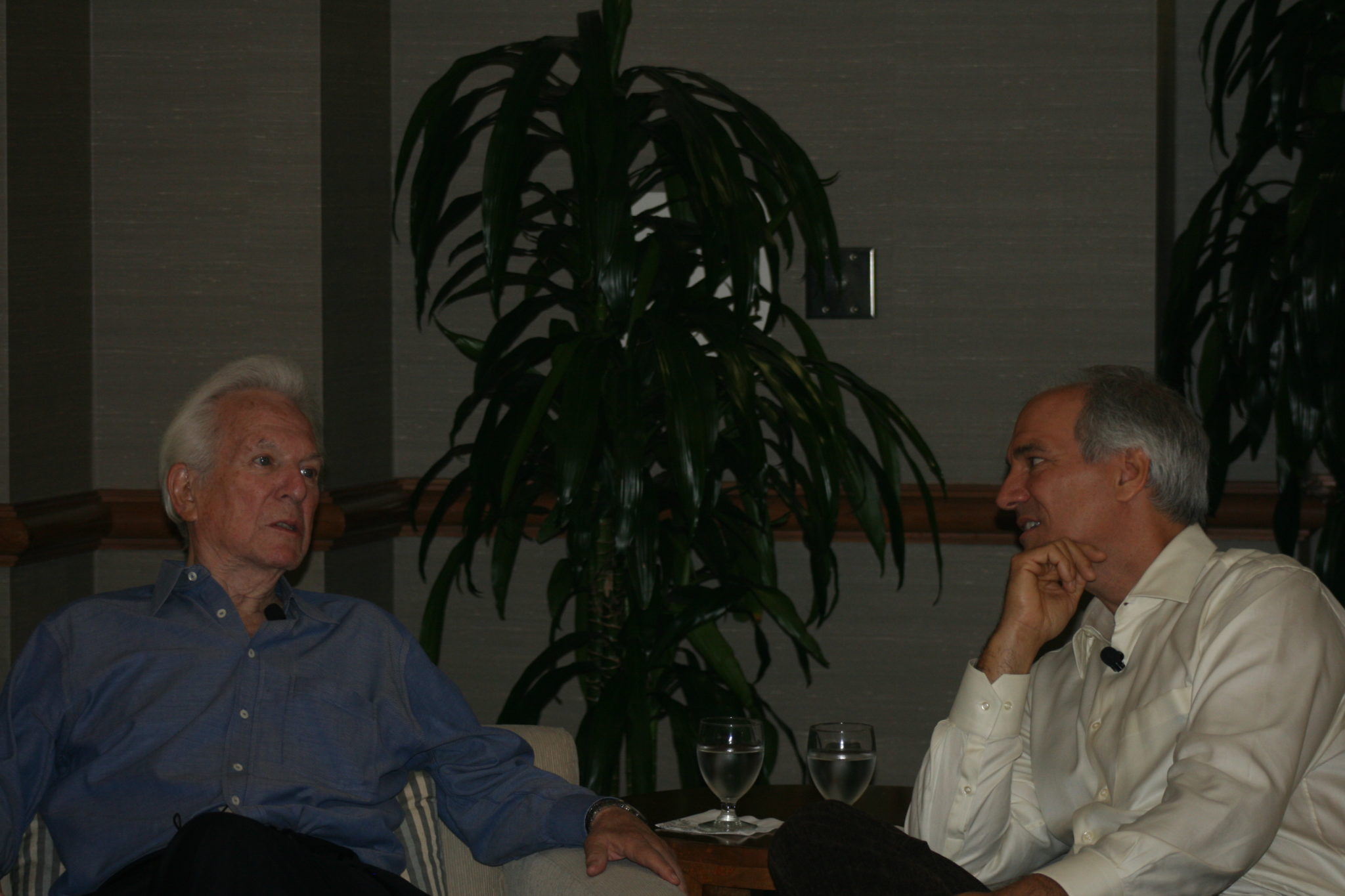

I have never known anyone who so consistently fought to squeeze the most joy and happiness from life as did Nathaniel. His condition worsened over the past several years, and over lunch with him and his wife Leigh a couple of years ago, he said to me, “The hardest thing is to not go around being pissed off all the time, because I can’t do things now that I could do perfectly well a couple of months ago.”

But the thing is, he didn’t walk around pissed off all the time. He didn’t walk around pissed off at all – though I know he had his moments. He took his situation not as a reason to surrender and feel awful, but as a challenge to meet as best as he could. He was always willing… no, he was always eager, to accept what’s true, to learn from his mistakes, from conflicts, from hardships; whether they were self-inflicted or thrust upon him.

Nathaniel was a resilient man, a happy man, a complicated man; a good man.

Aristotle said that happiness is the meaning and purpose of life, the whole aim and end to human existence. Nathaniel embraced this.

I know that others have had different experiences of him in his earlier years, and I’m sure since. But for me, Nathaniel was a profoundly warm, kind, and challenging friend. I was not always completely at my ease around him, particularly when I was younger. He challenged me to feel deeply, think clearly, love profoundly, work and create doggedly; to look for the best in others, and to bring my very best to the world. He was a man who lived with passion, humor, and integrity.

His life has been an inspiration for those of us longing to live life that fully, that joyfully. I think I remember that Ayn Rand signed one of her books to him saying, “To the boy on the bicycle.” To those who’ve read The Fountainhead, you know that the boy she’s speaking of is the young man with whom Howard Roark has a brief encounter, and in doing so fills that young man with a sense of life as it could be lived; as it should be lived – with “the courage to face a lifetime.” If Ayn Rand had that effect on Nathaniel – and I know that she did – Nathaniel has multiplied that effect many times over in those whose lives he’s touched.

I know I’m not alone in saying that Nathaniel Branden inspired me with a sense of life as it could be lived; as it should be lived. Because he lived it himself. Through all the drama and the tragedy and the passion and the excitement and the love and the success… and even through the decline; he lived it himself.