Translating deep thinking into common sense

The New Epidemic of Fictitious Campus “Rapes”

By Walter Donway

September 18, 2018

SUBSCRIBE TO SAVVY STREET (It's Free)

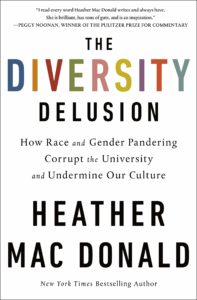

Part II of a three-part book overview of:

The Diversity Delusion: How Race and Gender Pandering Corrupt the University and Undermine Our Culture by Heather Mac Donald: New York City: St. Martin’s Press, 2018.

Part I of the book overview was titled “High-Tuition Tribalism.”

“… 73 percent of the women whom she characterized as rape victims said that they hadn’t been raped … 42 percent of … supposed victims had intercourse again with their alleged assailants.” – Heather Mac Donald

Heather Mac Donald

Source: Manhattan Institute

A funny place, today’s American college campus, says Heather Mac Donald. The huge, vigilant bureaucracy put in place to manage the most intensive crime wave ever reported—campus sexual assault on co-eds—insists that the problem is underreported.

But, if the reports and/or estimates of rape on campus are even remotely accurate, then there would be as many as 400,000 sexual assaults on undergraduate women every year. As Mac Donald points out, parents would lock their daughters in the attic before allowing them to enter these hellholes of lust and criminality. But, of course, parents harbor no dearer dream and ambition than for their daughters to be admitted to these institutions. Don’t they care?

Funny, too, that often rapes are reported several months after they occur, when the victim discovers that what happened to her on that date was rape. What she seldom if ever does (nor do the workers of the academic rape industry) is report the crime to the police. If, in the outside (real) world, a large percentage of rapes go unreported, then on campus almost no rape is reported to the police—only to campus bureaucrats and to government agencies set up to track campus rapes (and penalize campus programs that report too few).

The “Gender” Industry

Funny, too, that often rapes are reported several months after they occur, when the victim discovers that what happened to her on that date was rape.

In the second major section of her recently published book, The Diversity Delusion, Manhattan Institute senior researcher, Heather Mac Donald, gives us the bad news:

The racial diversity of students is not the only obsession that today is shoving aside the traditional mission of the university: scholarship and teaching. Shoving it not only out of the curriculum—to be replaced by courses about race, ethnicity, diversity, minority leadership, and “power relations”—but shoving it out of the budget, is what Mac Donald calls the “diversity industry” that grows even in periods of budget stringency.

Right along with the diversity industry is the “gender” industry.

Mac Donald argues that the American university’s latest manifestation of the feminist movement—a movement now focused almost solely on supposed oppression of women by a patriarchal society—in fact began with an earlier and almost opposite feminist movement. In the cherished memory of (some) baby boomers, the 1960s was the decade of the sexual liberation, including of women. Liberated to be just as sexually assertive, sexually active, as men always had been. It was time to fling aside the chafing constraint of male expectations for women, time to abort the unwanted baby, and burn the bra.

But first, Mac Donald says, a long-standing conviction about human nature had to be jettisoned: the notion that the different physical biology of men and women correlates with an objectively different sexual psychology. Like any human characteristic, that sexual psychology existed within a spectrum of individual variation.

But the principle had been observed for centuries or millennia. Men focused on the sexual aspect of male-female interaction, approached new relationships with a sexual agenda, sought sexual conquest, and could move without emotional baggage to the next relationship. Women focused far more on the emotional aspect of the male-female interaction, sought emotional intimacy as a context for sex, and invested themselves in commitment to a partner.

What crap! What an attic full of quaint, dusty, leftover Victorian-era furniture! Men and women were equal and equal meant the same. Women wanted sex, too! Lots of it! And “It don’t even matter who you waken with tomorrow …”

What happened to liberation? It is not gone, Mac Donald assures us. But a “central tenet of the campus rape movement is that one fifth to one quarter of all college girls will be raped or be targets of attempted rape by the end of their college years.”

MacDonald writes: “The campus rape movement highlights the current condition of radical feminism from its self-indulgent bathos to its embrace of ever more vulnerable female victimhood.”

What happened to liberation? It is not gone, Mac Donald assures us. But a “central tenet of the campus rape movement is that one fifth to one quarter of all college girls will be raped or be targets of attempted rape by the end of their college years.” The claim appeared first and most prominently in Ms. Magazine in 1985. By now, it has been repeated thousands of times in academic studies, government supported surveys, university publications, and women’s magazines. And the ante keeps rising: Even as the consultants, and permanent new staff, swarmed onto campuses—to recommend, organize, and manage the campus rape centers and the whole apparatus for dealing with omnipresent sexual assault—estimates of the incidence of such assaults kept rising. The mantra became: It is under-reported. Always, everywhere, under-reported.

What was going on?

Reinventing Rape

“The baby boomers who demanded the dismantling of all campus rules governing the relations between the sexes now sit in the dean’s offices and student-counseling services. They cannot explicitly repudiate their revolution. … Campuses have created a bureaucratic infrastructure for responding to post-coital second thoughts more complex than that required to adjudicate maritime commerce claims in Renaissance Venice.” – Heather Mac Donald

The crime of rape, and sexual assault generally, was being reinvented by the feminist movement. And a big part of their problem was to explain to women students how to know when they had been raped. On the outside (in the real world), a woman, unless unconscious, knew when she had been raped. It really was difficult to miss.

The crime of rape, and sexual assault generally, was being reinvented by the feminist movement. And a big part of their problem was to explain to women students how to know when they had been raped.

On the outside (in the real world), a woman, unless unconscious, knew when she had been raped. It really was difficult to miss. It was terrifying, emotionally revolting, and left psychic scars that could inhibit sexual relationships for a lifetime. And women did not telephone their rapist the next morning to boast about the intensity of their orgasm, or ask when he had “come”—or plan the next date.

On campus, a long process of education began to convince women that they were in a danger zone: because the very nature of the male-female relationship in American society was historically oppressive, a male patriarchy maintained to dominate women—in the family, in school, in the workplace, in government, in bed. Nowhere was this oppression more apparent and primitive than in the sexual predation of the young undergraduate male.

Okay, then, maybe it would be a good idea to set some limits to male-female interaction. Perhaps a self-imposed curfew by women. Advice against going to a man’s dormitory or fraternity bedroom. Counsel limiting drinking at parties. Certainly, rules requiring separate dormitories for men and women. Might not be a bad idea to experiment with single-sex women’s colleges.

Okay, then, maybe it would be a good idea to set some limits to male-female interaction. Perhaps a self-imposed curfew by women. Advice against going to a man’s dormitory or fraternity bedroom. Counsel limiting drinking at parties. Certainly, rules requiring separate dormitories for men and women. Might not be a bad idea to experiment with single-sex women’s colleges.

Never! What about the sexual revolution? The glorious liberation of the 1960s? The identity of male and female sexual psychology? No, the feminism of the ‘Sixties sexual revolution, and today’s feminism of the female victim of the patriarchy, exist side by side. “The academic bureaucracy is roomy enough to include both the dour anti-male feminism of the college rape movement and the promiscuous “hookup” culture of student life.”

Mac Donald is aware that the philosophical/ideological origins of the academic obsession with “identity”—racial, ethnic, and sexual—lie in Postmodernism, the counter-revolution arising in German philosophy against the Enlightenment ideas of reason, objectivity, individualism, human rights, and the market economy. She touches upon how Postmodernism, sometimes called neo-Marxism, has swept American campuses with an ideology that divides people into “identity” collectives, groups that everywhere relate as oppressors and the oppressed. And, indeed, when she comes to discussing multiculturalism and the subversion of the university’s mission to transmit knowledge, Postmodernism comes to the fore (Part III of this review).

But the rape movement could not have gripped the minds of a generation of college students, faculty members, and staff without some plausible, observable problem. And there is a problem: the profound conflict, the dilemma, of young women living in a culture of sexual promiscuity—one-night stands and “love’em and leave’em—and indoctrinated with the sexual-liberation premise that they want and need this because they are no different than the men who purportedly want and need it.

Mac Donald describes many incidents, ranging from humorous (at least to the outsider) to wrenching to disastrous (when men get ensnared in the campus “justice” system, or, very rarely, the real justice system). But the pattern tends to be the same. The young woman heads off to date, to party, or to “trip.” At some point, usually sooner rather than later, alcohol enters the picture. Today, liberated women, in the long tradition of college men, decide to get “smashed,” “shit-faced,” “blotto” with the same sense of naughtiness, bravado, long familiar to men. Sex occurs, drunk or sober—occasionally passed-out—and, not necessarily the next morning, or the next week, or even month, the woman, especially if she is angry and hurt that the man moved on to another woman, begins to feel victimized. She may have been high, drunk, or half-asleep. She doesn’t remember resisting the man, but she doesn’t remember saying “go ahead,” either.

But now, the university’s student handbook, and certainly the mores of the sexual-assault “response team,” spell out whose consent, in what form, at what stage is required for “consensual” sex to occur.

Or sometimes we have a lesser offense. “In 2014, federal authorities changed the reporting category of “Sex Offense—Non-forcible” to the inherently vague “Fondling.” Voila! The reports increased 6,000 percent, from 59 non-forcible sex offenses in 2013 to 3,414 fondling incidents in 2016.” Hooray, now we have the evidence to fit the narrative.

We old-time alums can be grateful for the statute of limitations. (Wait, maybe there isn’t one on campuses …). I think that I did some fondling in my time. I think that I still can hear “Mr. Tambourine Man” playing in the background.

But the campus sex police do not have a sense of humor. The Office of Civil Rights of the U.S. Education Department under President Obama, in 2011, sent what is now called a “Dear Colleague Letter” to warn every college and university to weaken their “due-process” rules in campus rape tribunals if they didn’t want to lose their federal funding. Presumably, they were letting their male students off too easy and burdening their female students with arduous standards of proof.

They were told that in such proceedings a “preponderance of the evidence” (51 percent) would be just fine; no need for some legalistic rigmarole about “beyond a reasonable doubt.” Four female Harvard law professors, to their credit, filed a complaint with the Office of Civil Rights in August 2017. The letter, they wrote, resulted in procedures for dealing with accused rapists (so common among Harvard undergraduate men) that were “frequently so unfair as to be truly shocking.”

Drunk on the New Feminism

In understanding how academics construe the concept of “justice,” and the kind of justice system they would like to see, it is instructive to look at campuses. Women apparently are utterly without responsibility for their actions when drunk, including so drunk that later they can’t remember anything. Not only is the woman not responsible for what happens at the moment sexual activity actually begins, she is not responsible for the decision to drink, how much to drink, and where to go when drunk. Mac Donald quotes a Columbia University security official marveling at the scene at homecomings: “The women are shit-faced, saying ‘Let’s get as drunk as we can,’ while the men are hovering over them.”

The man is the only one of the pair responsible for what happens when both are incapacitated by alcohol. “Thus do men again become the guardians of female well-being,” writes Mac Donald.

But postmodernist doctrine, including the new feminism, is that men have all the power; they call the shots; and they are responsible. The man is the only one of the pair responsible for what happens when both are incapacitated by alcohol. “Thus do men again become the guardians of female well-being,” writes Mac Donald.

Seemingly appalled at the world created by the sexual liberation movement of the Sixties, “The university is sneaking back in its in loco parentis oversight of student sexual relations, but it has replaced the moral content of that regulation with supposedly neutral legal procedure.”

Campus authorities are now organized voyeurs of student sexual activity, requiring the most detailed account of who touched what, and when. This is supposedly a responsible inquiry into serious crimes and, often, the goal is to “help” the female student to understand that she was raped.

Campus authorities are now organized voyeurs of student sexual activity, requiring the most detailed account of who touched what, and when. This is supposedly a responsible inquiry into serious crimes and, often, the goal is to “help” the female student to understand that she was raped. As quoted at the beginning of this article, women may tell all—angry at the man and with the embarrassment of having sex, being left for the next woman, and having to see the man in class every day—but rarely will agree to level the charge of legal rape and involve the police.

That is not surprising. In most cases, a woman would feel foolish (or worse) trying to convince a police officer she had been raped. In case after case where police have been called in (including the famous rape charges, later dropped, against a group of men at Duke University), they have found no credible evidence of a crime. Because the rape movement has redefined beyond recognition the crime and the rules of evidence.

“The due-process deficiencies of campus tribunals have been glaring. As of early 2018, seventy-nine judges had issued rulings against schools’ rape trial procedures.”

Indeed, one of the most effective retorts to the entire campus rape machinery is that rape, real rape, is far too serious a crime to swaddle in college “encounter group” hearings.

If it is rape, it should be reported to the police.

Postmodernism from Socialism to Self-Pity

But Mac Donald demonstrates, as we shall see in the final part of this overview, that postmodernist ideology puts awareness of group identity and “oppression”—including sexual oppression—at the core of education. Who needs English literature (“by dead white men”) or the history of Europe when you live daily under oppression? Who needs to study opera or poetry (more “dead white men”) when you are caught up in an epidemic of rape?

Obviously, the rape industry has escaped from campus into the culture at large. Mac Donald discusses the explosive appearance of the #MeToo crusade, by means of which academic feminism is gaining a virtual monopoly on mainstream discussion of the sexual relationship.

Obviously, the rape industry has escaped from campus into the culture at large. Mac Donald discusses the explosive appearance of the #MeToo crusade, by means of which academic feminism is gaining a virtual monopoly on mainstream discussion of the sexual relationship. If the campus rape movement reduced actual rapes that would be a gain, obviously. And if the #MeToo movement reduced sexual exploitation in the workplace, says Mac Donald, that would be welcome.

That is unfortunately unlikely because neither the campus rape movement nor the #MeToo movement is about protecting women. It is about what the Old Left called the process of “radicalizing” the worker. Use an experience of injustice, real or (as today) largely imagined, to convert people to systematic, activist, and increasingly violent adherence to a political ideology.

In the case of Postmodernism, the ideology is anti-capitalism, a bedrock of the Marxism view of society as a relationship between the oppressor and the oppressed. Yes, the #MeToo movement might reduce workplace sexual exploitation, writes Mac Donald, but “Its likely results … will be to unleash a new wave of gender quotas throughout the economy and to mystify further the actual differences between males and females.”

The #MeToo quota effect already is being dramatized in Hollywood, of course, with pressures from feminist, LGBTQ, and disability activists to hire by identity category. But the neo-Marxist vision of a revolt against capitalist (now also the “Western” and “patriarchal”) oppression is everywhere from Silicon Valley to the National Gallery of Art. And, of course, ubiquitous in academic departments, the citadels of Postmodernism.

For example, the ”trans” movement now probably trumps feminism, Mac Donald observes, with its official beginning when “The New York Times ran a full-page editorial declaring the oppression of the transgendered one of our most pressing civil rights struggles.”

The transition from a new cause to a politically correct absolute has been shortened drastically: “An issue that didn’t exist a short time ago is now completely settled in the minds of the cultural elite; anyone who opposes the new regime is simply an atavistic, benighted bigot.”

As always, politics and psychology converge because rational or utterly irrational, the philosophy that shapes the future of cultures and countries is more or less internally consistent. A view of reality and man’s means of knowledge, of the world and human nature (including human psychology), underlie a view of the nature of morality, society, and politics. At the roots of Postmodernism is the view of man as unable to know reality, unable to know truth, and so unable to communicate objectively with others. It is an illusion that we act on our ideas or interact with others on the basis of our ideas. What is important about us is our inherent identity. And this becomes a war of oppressors and oppressed until egalitarianism reigns. Therefore, the postmodernist political pole is socialism (which universities have not failed to inculcate in recent generations); its personal psychological pole is victimology. After all, if we are victims, and victims are the focus of caring and (“social”) justice, then the immediate incentive of the postmodernist is to join the ranks of the oppressed.

“Finally, we see that narcissistic students are now coequal drivers with their professors when it comes to rapidly evolving victim theory. By one count there are now 117 categories of gender identity, many of those developed by students struggling to find some last way to be transgressive in an environment where their every self-involved claim of victimhood is met with tender attention and apologies from the campus diversity bureaucracy.”

Today, for the price of a four-year college education (until left Democrats make all higher education a government-paid “right”), your son or daughter can learn to become a life-long victim. Of course, many—even most—will not. There is still such a thing as self-esteem.

The usually once-in-a-lifetime college years of challenge, enjoyment, and accomplishment that are the incredible privilege of today’s students will be diluted—and squandered—on a political agenda.

But even the student who rejects victimhood will get four years of indoctrination in the role of oppressor or oppressed. And that indoctrination, as Mac Donald shows in the final sections of her book, will replace much of the time once devoted to engaging with learning, with the priceless legacy of culture—scientific, humanistic, and artistic—with which our society entrusts the professoriate. The usually once-in-a-lifetime college years of challenge, enjoyment, and accomplishment that are the incredible privilege of today’s students will be diluted—and squandered—on a political agenda.

Mac Donald is none too gentle with the perpetrators:

“Those privileged cowards can’t even summon the guts to prescribe the coursework that every student must complete in order to be considered educated. Need it be said? Students don’t know anything. That’s why they’re in college.”