Translating deep thinking into common sense

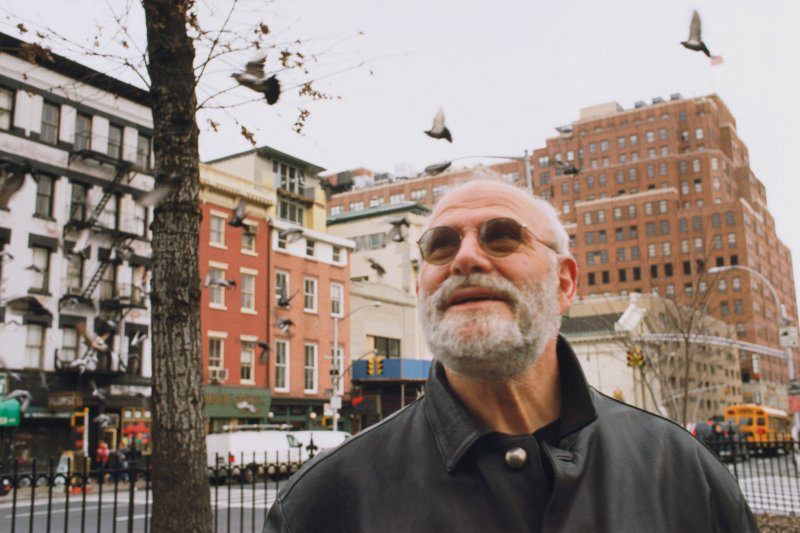

A Legendary Neuroscientist Says “Goodbye”

By Walter Donway

February 21, 2015

SUBSCRIBE TO SAVVY STREET (It's Free)

Today, February 19, in a contribution to the Op-Ed page of the New York Times, our era’s most profound student of human consciousness—as seen from the perspective of people who live with afflicted brains—announced that he is dying. He began: “A month ago, I felt that I was in good health, even robust health. At 81, I still swim a mile a day. But my luck has run out–a few weeks ago I learned that I have multiple metastases in the liver…” (http://www.nytimes.com/2015/02/19/opinion/oliver-sacks-on-learning-he-has-terminal-cancer.html?emc=eta1)

Oliver Sacks is one of the world’s great lovers. Not, certainly, a Romeo or Casanova; he admits in an interview that he has been celibate for decades and calls his peculiar shyness a “sickness.”

Oliver Sacks is one of the world’s great lovers. Not, certainly, a Romeo or Casanova; he admits in an interview that he has been celibate for decades and calls his peculiar shyness a “sickness.” No, Sacks’s love affair is with existence as viewed by a scientist: its stuff and its astounding secrets, most of all, those of human consciousness: how the human mind functions at its supremely best—in creating ravishing music—and when it must adapt to catastrophe—as when disease locks it into speechless catatonia for decades.

The love affair began before Sacks was five years old, growing up in London in a Jewish family, his father a physician, his mother one of the first female surgeons in England. In his autobiography, Uncle Tungsten: Memories of a Chemical Boyhood, he begins on page one with scientific wonder: “Many of my childhood memories are of metals; these seemed to exert a power on me from the start. They stood out, conspicuous against the heterogeneousness of the world, by their shining, gleaming quality, their silveriness, their smoothness and weight. They seemed cool to the touch, and they rang when they were struck.” (Vintage, 2002)

Some would say Oliver could not have missed becoming a renowned scientist. He was born into a huge Jewish family (his mother was one of 18 children) started by a 16-year old boy who escaped Russia on the passport of a dead man and ended up in London, where he launched the family that seemed to spawn brilliance and success in every generation. With two physicians for parents, Oliver’s endless, surely maddening questions about “everything on Earth,” were answered mostly with enthusiasm and challenge.

And yet, the boy who became his era’s most popular and beloved (yes, that over-used term applies) writers about human consciousness, the human condition, and the mind under every medical assault did not have a charmed boyhood. Although not everyone would react as he did, he had reason for lifelong empathy with struggle. During the Nazi bombing of London, he and his older brother were shipped out of London for four years to a boarding school where they were fed animal fodder (food packages from home were confiscated) and caned by a headmaster who delighted in lashing bare bottoms—Sacks says especially his—until boys could not sit down normally for weeks.

Confession: I have not finished reading Sacks’s first memoir, Uncle Tungsten, but I know of Sacks’s career and writings, have read some of his books, and had the pleasure of meeting him and hearing him speak. In a way so typical of his generosity, he endorsed my new Dana Foundation publication, Cerebrum, giving it a publicity handle that meant much.

Some readers will know that Sacks became a neurologist, first qualifying for medicine at Oxford University, then re-qualifying in the United States; has practiced neurology in New York City since 1965; and became our era’s foremost ambassador to the invisible world of mental institutions and the conditions of human consciousness—unbelievable even as we read about them—that imprison our fellow human beings there for decades, even a lifetime. He is our ambassador because he has written about his work, but, above all, his patients, in book after book—almost all now best-sellers—to explain the science, and the human tragedy and triumph, behind some of the most mystifying human afflictions ever recorded.

In 1973, Sacks published Awakenings about his work at Beth Abraham Hospital in the Bronx, New York City, with catatonic, motionless and speechless patients who survived the 1917–28 epidemic of encephalitis lethargica and had been warehoused alive but utterly cut off from the world for decades.

In 1973, Sacks published Awakenings about his work at Beth Abraham Hospital in the Bronx, New York City, with catatonic, motionless and speechless patients who survived the 1917–28 epidemic of encephalitis lethargica and had been warehoused alive but utterly cut off from the world for decades. This, after all, was half-a-century after the end of the epidemic…

Sacks hypothesized that a new drug, L-dopa (now universally used to treat Parkinson’s disease), might awaken the muscular control and connection with the world of these patients who had been “stored” for decades by a society that would not allow them to die. The L-dopa worked, call it “miraculously,” but what do you do with a man or woman who “awakes” after four decades of utter disconnection with any passage of personal or world history? How do you deal with the sheer bewilderment, terror, and lack of comprehension? That is the story told by Oliver Sacks in Awakenings, a book that arrested the imagination of film makers (a 1990 film starring Robin Williams, nominated for three Academy Awards) and playwrights (Harold Pinter).

I don’t think that Sacks expected such publicity, but Awakenings and more than a dozen books since then have caused him to be described as the most celebrated and reported neuroscientist of our time. I have read some of his most famous works, including The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat (1985) and An Anthropologist on Mars (1995). The first is about those conditions of the brain, sometimes only a very limited part of that brain, that manifest as distortions of consciousness: inability to identify faces, inability to form any new memories (like the otherwise normal man with Korsakoff syndrome who in 1970 had formed no new memories since the end of WWII), and lack of proprioception (like the woman who had no sense of the position of her body parts in space. The second is about Temple Grandin, a woman born autistic (with what we now call Asperger’s Syndrome) who became the most accomplished, widely known, and famous writer and speaker about autism.

You cannot grasp the influence of Sacks as our ambassador to (and from) the world of the altered brain without reading at least one of his books.

You cannot grasp the influence of Sacks as our ambassador to (and from) the world of the altered brain without reading at least one of his books. He remains, in a sense, the quintessential physician and British writer. The great physicians of the last century, and even today, are acute observers of human beings, schooled to proceed from observation to deduction—and then to speculation. Indeed, Sacks has been criticized, on occasion, for using observational reports and anecdotes where other scientists demand quantitative measurement.

It is true that measurement, double-blind trials, and quantitative reports are the gold-standard in science and, of course, medicine. But that stage of investigation rests upon observation and description. The conditions that Oliver Sacks describes with acuity and boundless empathy are not yet susceptible to measurement and quantification. Today, only the sensory level of consciousness approaches the stage of definitive measurement. It would be the rash neuroscientist who claimed that only double-blind trials were permissible in the study of higher functions of consciousness such as creativity.

The career of Oliver Sacks has been typical of New York City, where so many world-class institutions in medicine and science compete for practitioners. Sacks has gone from Beth Abraham Hospital at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine to New York University School of Medicine to Columbia University Medical Center, and back to NYU. But throughout, since 1966, he has continued to work in that supposedly dreary medical dead-end, nursing homes, as a neurological consultant to facilities maintained by the Little Sisters of the Poor. There, as elsewhere, he has found “in cold storage” the men and women institutionalized with afflictions of the brain that produce arresting alternatives to normal consciousness that fascinate, move, perhaps terrify the worldwide audience for his books. In those books, real men and women are the actors in the drama of the human mind striving to adapt to virtually any compromising affliction.

And now, Dr. Sacks has told us that his days are numbered. He does not make much of it, publicly, but he is an atheist—which is only to say that he is a true scientist. As a kind of footnote, an afterthought, the Wikipedia article on Sacks lists, last, that in 2010, he was named to the “Honorary Board of Distinguished Achievers” of the Freedom from Religion Foundation.

As he looks toward death, he relates how luck, what we can or cannot control, plays its part. Ten years ago, when he was 70, he was diagnosed with a rare tumor, a melanoma, of the eye. Radiation and laser treatment seemed to kill the cancer, but also his sight in that eye. And so medical science gave him another 10 years of life that he spent in active practice, writing and publishing, and love—the love of understanding the human condition.

But now, he says, good luck has been followed by bad luck. Only two percent of cases of ocular melanoma, when apparently treated, tend to metastasize. His did and now his liver is cancerous—a form of cancer that may be slow, but is untreatable and always fatal. He reckons his time left in months.

“I feel intensely alive, and I want and hope in the time that remains to deepen my friendships, to say farewell to those I love, to write more, to travel if I have the strength, to achieve new levels of understanding and insight.”

“There is no time for anything inessential. I must focus on myself, my work and my friends. I shall no longer look at “News Hour” every night. I shall no longer pay any attention to politics or arguments about global warming.

“This is not indifference but detachment — I still care deeply about the Middle East, about global warming, about growing inequality, but these are no longer my business; they belong to the future.”

What a liberation! Leave the news hour, and ISIS, and even “global warming” to the future. I hope I have inspired some readers to turn to this heroic message from one of the greatest among us—and then to read his books. I most certainly will do so.

Not having read all of what Dr. Sacks has written, I don’t know what wider conclusions he has drawn from his work. To me, there are two broad and heartening generalizations. I do not attribute them to Dr. Sacks.

One is that consciousness arises from the brain, and, according to the brain’s structure and health, that consciousness varies in the most astonishing but ultimately explainable ways. That does not mean that consciousness necessarily is only the states and actions of the brain—the theory called “reductionism”—but that consciousness, whatever it is, is caused by the brain and likely inseparable from it.

The other is that human fate, the fate of the living, cannot be divorced from the accidents of the brain, from all those afflictions of the most varied, profound, and at times unimaginable kinds that determine the human condition. We need not consider their misfortune a mortgage on our lives and search for happiness, but, if we ignore their plight, we cannot know, not fully, that our own happiness is rooted to some degree in chance—though what we do with our good fortune, and Dr. Sacks is the supreme example—owes to our determination, choice to love this world, and to that greatest of classical virtues, courage.

Dr. Sacks writes: “I cannot pretend I am without fear. But my predominant feeling is one of gratitude. I have loved and been loved; I have been given much and I have given something in return; I have read and traveled and thought and written. I have had an intercourse with the world, the special intercourse of writers and readers.

“Above all, I have been a sentient being, a thinking animal, on this beautiful planet, and that in itself has been an enormous privilege and adventure.”