Translating deep thinking into common sense

Part II: A Post-Randian Analysis of Musical Meaning

By Roger E. Bissell

October 16, 2023

SUBSCRIBE TO SAVVY STREET (It's Free)

Editor’s Note: This is Part II of a three-part essay on: “Toward an Objective Aesthetics of Music.”.[1] Part I was titled “Extending Ayn Rand’s Aesthetic Theory to Music.”

For those who prefer audio/video, some of these ideas were also discussed on The Savvy Street Show Episode 14, “Music and Objectivism.”

3: A Musical “Theory of Everything”?

Here we must make one more stop before actually doing some song analysis in order to underscore the fact that there are several things that the rest of this essay will not try to do. For one thing, I will not be attempting an encyclopedic analysis—or even a whirlwind sketch—of all aspects of all musical works for several reasons.

First, I will be looking specifically and exclusively at melodies and musical themes from Western music. (I include in this the substantial body of high-quality popular and theater music created in the past century by African American, Jewish American, and other songwriters and composers.)[2]

While both music and literature are temporal arts, unfolding across a span of time, not all literature tells a story, and neither does all music.

Now, to some, this is a humanistic no-no. In this day and age of multiculturalism and inclusivity, failing to properly consider the creative endeavors of other countries is tantamount to parochial narrow-mindedness, if not outright xenophobia and bigotry. However, and meaning no disrespect to music from other cultures, such as those in Asia or Africa, I am interested first and foremost in understanding the music that I grew up hearing and performing—and wondering about!—and so that’s the music I will focus on here.[3]

Like most of my readers, I am sure, I have already established an experiential beachhead, as it were, on the shores of Western music, itself a vast continent of musical creations. At my increasingly tender age, I don’t have enough time and resources to wage a multi-front campaign in order to keep from offending people who wouldn’t even know or care if I didn’t write this essay at all! So, if I and others are successful putting our first and best efforts into following the admonition to “Know thyself”—and “thy music,” i.e., the music of the richly populated half-millennium of Western tonal music—then perhaps someday others following in my footsteps can better be able to probe the meaning of music from other continents.

Second, beyond the line in the sand that I drew in Part I of this essay (in regard to symphonic and operatic music and the like), I want to cordon off two other categories of music that we will not be exploring in the conclusion of Part II. Specifically, while I do want to acknowledge the importance and worth of non-dramatic music—and in particular, music that is more poetic or more descriptive in its nature—I also want to set it aside for the purposes of this essay.

It’s generally recognized that there are several broad, distinct types of music, as is also the case in literature. While both music and literature are temporal arts, unfolding across a span of time, not all literature tells a story, and neither does all music.

Some literature is just poetic in nature, using rhyme and other techniques in order to convey its meaning. Other literature is descriptive in nature, using vivid language in order to convey its meaning. But still other literature (especially Romanticist) is goal-directed in nature, using a logically connected progression of events (i.e., plot) in order to convey its meaning. Some literature uses more than one of these, of course.

Music is the same way. Some music combines two or all three approaches, but many pieces are clearly one or another of these three kinds. Poetic and descriptive music, like dramatic, goal-directed music, can be analyzed and their emotional meaning understood, but since the former do not fall under the rubric of goal-directedness, they are not directly relevant to the philosophical meaning of pursuit and achievement of values that is embodied in the songs we will be examining in the conclusion. Let’s look briefly at some examples of each, in lieu of a deeper dive into poetic and descriptive music.

Poetic and descriptive music, like dramatic, goal-directed music, can be analyzed and their emotional meaning understood.

Some music, such as the dance forms, sonatas, and symphonies of the 18th century (i.e., the pre-Classical era), as well as many songs throughout history, are mostly (though not exclusively) poetic. Although they incorporate harmonic progressions, and to that extent have what may be regarded as having some discernible amount of “musical plot,” they are not nearly as developmental and exploratory as later music, in the Classical and Romantic eras, and hence what drama they have in them is rather muted and soft-spoken.

In particular, consider Handel’s Messiah or Bach’s third Brandenburg Concerto, which are both very interesting, even rousing pieces, but with “an interest based on elaboration, symmetry, and rhythmic pulse, rather than upon progress…. Dramatic development has no part to play” (Anthony Storr, Music and the Mind, 1992, pp. 82, 81, emphasis added). Other examples: Mozart’s Rondo ala Turk, and Dave Brubeck’s Blue Rondo ala Turk, and Claus Ogerman’s album Piano Concertos. The beauty, excitement, and general value of such music is conceded, but such pieces are simply set aside for the purpose of this essay, which is to explore the nature of the emotional power of narrative music.

Other music, such as Richard Strauss’s “tone poems,” Debussy’s Nocturnes, Gil Evans’s Sketches of Spain, or Claus Ogerman’s Cityscapes, is mostly (though not exclusively) descriptive. Such pieces emphasize the sensuous qualities of sound and are “more like a lyric tableau than a narrative action. Debussy in general tends to avoid patterns that strongly suggest goal-directed action.” (Leonard Meyer, Style and Music: Theory, History, and Ideology, 1989, p. 269) This music, too, can be very worthy and enjoyable, but in this essay our concern is with understanding how emotions are evoked by music that “tells a story.”

After all, it is the undeniable emotional effectiveness of narrative, “storytelling” music that has prompted the debate, which has raged for nearly two centuries, over whether, and just how, music can function as a “language of the emotions.”[4] Examples of such music include many of the sonatas, symphonies, concertos, preludes, nocturnes, etc., even songs, of the 19th and 20th centuries.

Ironically, this kind of music, which was most similar in form to the literary novel, was the prime force that “encouraged the development of orchestral concerts in which music was entirely unrelated to words.” This kind of music “provided an equivalent for dramatic action: a story in sound which had a definable beginning, middle, and end…the pattern of contrast, conflict, and final resolution…” (Storr 1992, p. 81)

This kind of music primarily conveys whether man is good, whether man is in control of his destiny, whether values can be achieved, and whether happiness is possible—the kinds of issues highlighted by Rand in The Romantic Manifesto as most fundamentally significant about life and the world—and this is the kind of music that we will be focusing on in this essay. As such, we will spend very little time analyzing or looking at more purely poetic or descriptive music, which is a lot of music. To the extent we do so at all, it will be to help the reader understand better why such pieces do not have the same kind of dramatic, emotional content as narrative music.

Now let’s consider the second main reason for this essay’s taking a narrower focus. First of all, a full analysis of the entire musical output of the human race, even if possible, would be an incredibly vast project. One such suggested project was outlined by Ayn Rand in her essay “Art and Cognition,” in which she proposed that researchers carry out:

…a computation of the mathematical relationships among the tones of a melody—a computation of the time required by the human ear and brain to integrate a succession of musical sounds, including the progressive steps, the duration and the time limits of the integrating process (which would involve the relationship of tones to rhythm)—a computation of the relationships of melody to harmony, and of their sum to the sounds of various musical instruments, etc. [p. 61]

As Rand notes (ibid.), “[t]he work involved is staggering”—much too daunting to attempt in the early, exploratory stages of the kind of analysis we’re pursuing here, and largely irrelevant to the present project, anyway.

Rand’s goal for such research is to develop a standard for evaluating music based on how much integration a given musical composition achieves.

Rand’s goal for such research is to develop a standard for evaluating music based on how much integration a given musical composition achieves; but while there’s nothing wrong with wanting to know this kind of fact and level of detail about music, it misleadingly suggests that music is much more different from the other arts than it really is. In fact, Rand’s hypothesis and proposed research method could be applied just as well and fruitfully to literature as to music. Yet, such an investigation, even if revelatory of real patterns in literature or music, will only tell us things about the nature of our mental processing of the music or the literature, not about their meaning. Except, of course, to the extent that the mental processing, rather than the music itself, embodies the meaning—which appears to be Rand’s assumption. And again, if that’s not the essential truth about meaning and emotion in literature, why would it be so in music?

To be more precise, then, Rand’s proposal would be for an investigation based on the premise that cognitive processing is meaning, whereas true meaning is the object of such a process. It is true that in reading literature or listening to music, we are processing something, but the point is that we are processing something. And just as Rand rightly focuses on the something, the what, the subject, of the other arts, I think it is just as important to direct our attention to the something, the what, the subject, of music.[5]

While Rand is undoubtedly correct in saying that a vast amount of research, databasing, and categorizing could be done with classical and popular melodies and could reveal how pieces vary in the mental integration they allow us to achieve in listening to them, my own interest is in seeing patterns of what is in the music, not patterns of how we process it. The purpose in doing so is to allow us to apply the insights of Cooke, Meyer, and others to the attributes of music, in order to uncover the deep meaning of music—in order to see how the metaphysical value-judgments and philosophical meaning are embodied in those attributes, as a guide to understanding why we respond to music the way we do.

So, in the final section of this essay, we will certainly be looking at how melodies and themes work together in one piece compared with another, much as one considers which of two shades of orange is closer to red than to yellow. However, the massive undertaking Rand suggests is neither possible nor even necessary, in order to get a very large foot in the door in understanding the emotional power of melody.

Neither, therefore, as I’ve already suggested, does this essay aim at the musical equivalent of a “Theory of Everything.” That term comes from the field of physics, where the current quest is to find a “Grand Unifying Theory” to explain gravity, electro-magnetism, and the nuclear forces and how the universe evolved the way it did.[6] Such a longed-for theory goes way beyond Einstein and his theories of Relativity, who went way beyond Newton and his Theory of Universal Gravitation, who went way beyond Galileo and his Laws of Motion and Kepler’s Laws of Planetary Motion. (Don’t get me started. Oops, too late.)

By contrast, I envision my efforts, certainly those in this essay, to be more on the scale of what Galileo and Kepler did. I am deliberately making an extremely limited examination of certain features of certain aspects of a certain set of musical pieces (what I think of as small-form dramatic music) within the realm of Western music, trying to find out what “makes them tick” and specifically how they stir emotions in listeners—not how to explain the emotional effects of any and every musical piece from any culture and any point in history. Even so, this undertaking will draw from a great deal of musical material, both classical and popular.

Melody and harmonic goal-directedness are very important and valuable in providing “emotional fuel” to listeners of music.

Another thing this essay does not attempt is to provide a set of standards for evaluating all music as to its worthiness. My own operating premise is that melody and harmonic goal-directedness are very important and valuable in providing “emotional fuel” to listeners of music, and I thus give them primary consideration in the analyses to come, since those attributes relate strongly and directly to some of the most deeply meaningful issues that feed into one’s outlook on life.

However interesting it would be to argue the point, though, I am not saying here that such melodic and goal-directed (i.e., dramatic) music is better than music that functions similarly to landscape painting (“tone poems,” Impressionistic music) or poetry (Baroque dance forms, early Classical themes). I would not do this, any more than I would say that a novel is better than a poem or a painting. It all depends on context—i.e., to whom, and for what. To each his or her own, in other words.

Nor will this essay try to argue the case for why purposeful elements in music are better than non-purposeful elements, or why music with confidently assertive melodies are better than music with wistfully resigned melodies, or why music with coherent melodies and harmonic progression are better than incoherent music, or why music with successful resolutions of conflict are better than music in which such resolution is avoided or denied. These are basically the artistic counterpart of the cardinal issues at the foundation of the ethics one chooses: Do you value purpose or not? Do you value self-esteem or not? Do you value reason and understanding or not? Do you value happiness or not?

I trust that my readers know where they stand on the basic foundational (meta-ethical) issues, one way or the other. It’s not my job, nor my desire, to convert anyone to my point of view on those issues. In point of fact, any of these perspectives can be appropriate in a given song or theme, depending upon the context. As Leonard Peikoff argues in a fascinating lecture, even “great, though philosophically false” art can have “survival value” and thus be worth consuming.

This is also true in regard to the inner details of artworks. In literature, as a parallel to dramatic music, most people regard villains as evil, but they are a necessary evil in a dramatic story, as a foil to the hero, i.e., to serve as contrast and source of conflict so that the plot is more interesting. (See The Fountainhead or Atlas Shrugged.) Or, on a deeper level, an author might use an unhappy ending as a way of dramatizing how certain political or social situations are so inimical to human success and happiness that no other outcome is possible, despite the best efforts and struggling of the main characters. (See We the Living.)

Similarly, in music, contrasting themes are used to provide variety and conflict, which is developed and resolved in the course of the piece. 19th century sonata form is a particularly good example of this, though some popular songs also exhibit the pattern.

Vigorously defiant pieces beginning and ending in the minor mode are an obvious parallel to a portion of a novel in which “the bad guy” wins.

Vigorously defiant pieces beginning and ending in the minor mode are an obvious parallel to a portion of a novel in which there is an intense struggle against uncertain odds, and they convey the idea that there are no guarantees in life, that struggle can result in defeat. Listen to the first few seconds of the final movement of Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata. (Yes, that sonata. We’ll discuss it more in Part III.) This is all the more reason why it is so important that there are at least some examples of vigorously defiant pieces that end triumphantly in a major key!

Rather than speaking as advocate for any one particular subcategory of melodies and themes, therefore, my mission is to lay out chapter and verse on how each of these different stances toward life can be embodied in the attributes of a melody. This I will do in the remaining section, so that we will all hopefully end up with a better grasp on why we are experiencing the emotions we do when listening to dramatic music.

My aim, in other words, is to help us understand the phenomena, to figure out how dramatic music conjures up emotions. Again, however, my goal will not have been to prove which songs or themes were the best, in any philosophical sense, but instead to have assessed the relative effectiveness of the musical factors that contribute to their emotionality, and whether that had anything to do with their relatively greater status and longevity in the public’s affections. (This is the famous, or infamous, issue of “why does only some music stand the test of time?”)

In other words, I will be aiming at laying the groundwork for the aesthetic evaluation of the melodies of a wide range of songs—i.e., at the effectiveness by which they conveyed their emotional meaning.[7] This, of course, presupposes an identification of their emotional meaning—which, as I’ve stated, is the main point of this essay: to pinpoint the objective indicators of emotion in music, which requires that we focus on the attributes of music and identify the meanings they convey.

Even delimited in this manner, the task will be a big one—one, however, that I hope repays the efforts made by their having provided adventure and enjoyment for the reader!

4: Explaining Deep Meaning and Emotion in Music

In dynamic arts like literature and music, both the entities and their actions are basic, essential features of the subject of those artforms. Accordingly, both features are available to take on the role of embodying deep meaningfulness that the reader or listener can detect and respond to.[8]

Just as literature embodies ideas in the attributes and actions of characters, so does music embody ideas in the attributes and actions of the melody. In listening to music, we have the impression that the melody, as a virtual auditory character, seems to behave in the same way that we (or a literary character) might behave. In music, we identify with a melody and we see how it moves and acts in situations within that music and how we (or a literary character) might move and act similarly in a similar situation.

By its nature, and by the nature of art, music must operate symbolically and emotionally in much the same way as the other arts, especially literature.

That’s it, in essence. By its nature, and by the nature of art, music must operate symbolically and emotionally in much the same way as the other arts, especially literature. Whether you call it “identification” or “empathy,” that is the process, as I stated in my earlier argument that music is no more a “language of the emotions” than is literature or the other arts. And, not coincidentally, music is no less a “language of philosophical ideas” than is literature or the other arts. The rest is just principles, details, and examples, to which we now turn.

As you will recall, three of the metaphysical issues Rand names, and which I mentioned in Part 1 are: Is the universe intelligible, or not? Is man capable of achieving his values and being happy, or not? And is man capable of choosing and pursuing values, or not? To them, I will add one more (for a reason we’ll understand shortly): Is man capable of controlling and directing his actions, or not? (It might be implicit in the third question, but it will be helpful to consider it separately, anyway, as we’ll see.)

Rand considers the answers to these questions to be foundational for one’s informal, subconscious view of life, and also to be highly influential in the explicit philosophy of life that one develops, including not only one’s ethics and politics but also one’s aesthetics. She gives them fullest treatment in the first three essays in The Romantic Manifesto, but she also mentions them here and there in The Virtue of Selfishness in regard to ethics and politics, as I have mentioned in my forthcoming co-authored book, Modernizing Aristotle’s Ethics. Let’s address them here one by one, in terms of the attributes of music and how they might be embodied in a piece of music.

First, there is the issue of an Intelligible Universe. It’s nearly self-explanatory, and happily it doesn’t arise in modern popular music, so we won’t be analyzing examples here. But if you’re not familiar with either the “total serial” or “aleatoric” genres of modern serious music, you should check them out in order to see what unintelligible music sounds like. Here is an article with examples of aleatoric music, and here is an article explaining and illustrating serial music. (Or you can visit a busy construction site and listen with your eyes closed.)

Another blessedly tiny niche in modern music is ably represented by John Cage’s 4’33’’, which requires a silent “performance” of that length by the on-stage musicians. (Middle school ensembles have a cut-down version appropriate to their age level that is 1’17”.) It is at least related to unintelligibility, in that if one’s sensory portfolio were devoid of any stimulus whatever, one’s ability to grasp a coherent world would be disrupted and one’s consciousness would dissolve away entirely (as was discovered by sensory deprivation experiments conducted back in the 20th century). Outside of these few aberrations, however, the Intelligible Universe premise reigns in modern music, both popular and serious, so we will move on.

Secondly, there is the issue of Achieving Values or, more simply, Happiness. As Rand pointed out, understanding emotion in music is not as simple as noting that a piece in a major key is happy and that a piece in a minor key is sad. But while this is not the complete explanation of emotion in music, it is a very important part of that explanation. For instance, it’s the basic reason that you wouldn’t sing “Happy Birthday” in minor or play Chopin’s funeral march (cite work) in major—except as a joke, of course! (I fondly recall our Disneyland Band once playing “Zip-a-dee-doodah” in minor as a lark. Until our show director heard us and ordered us to desist!)

Helmholtz (cited in Part I) in 1863 convincingly argued that major harmony suggests positive emotions and optimistic moods, while minor harmony suggests negative emotions and pessimistic moods. The basic physiological source of this polarity rests in the properties of the musical overtone series and how our brains integrate major intervals and scale degrees, which are more central to the overtone series vs. minor intervals and scale degrees, which are not.[9]

In effect, minor harmony (such as a C minor triad: C-E-flat-G as its basic harmony) is telling the brain and the subconscious: you’re not as successful in integrating this as you were in that other, major-mode piece (with a C major triad: C-E-G as its basic harmony). Or, in metaphoric terms, the melody you’re listening to is not having as joyous or successful a day as that other melody. (There are important factors that modify this basic happy/sad polarity and which we will discuss forthwith, but the basic message of harmony is: major = success, gaining, enjoyment, while minor = failure, losing, unhappiness.)

Thirdly, there is the issue of Pursuing Values or, as I like to refer to it: Striving. Deryck Cooke in The Language of Music (1959) has helpful insights on this. As both Cooke and Lippman (cited in Part I) maintain, musical tones in a melody can be regarded in terms of whether the second tone is higher or lower in pitch than the first, and the tonal “movement” from one note to the next accordingly being referred to as “upward” or “downward.”

Cooke says that upward moving intervals and melodies suggest striving, aspiring, yearning, desiring—some sort of goal-directed perspective, some attempt to achieve values—while downward moving intervals and melodies, on the other hand, suggest a state of rest or acceptance or a settled mood, of consuming, or failing to consume, values. In general, melodies that exhibit upward motion are experienced as “asserting” or expressing an “outgoing emotion,” while melodies with downward motion are “accepting” or expressing an “incoming emotion.” (I prefer to think of them in terms of “investing” vs. “cashing-in.” Or, if you prefer an agricultural metaphor over a financial one: “sowing” vs. “reaping.” The idea is basically the same, however.)

Aristotelian scholar Fred D. Miller, Jr. reaches back to Ancient Greece for another psychological explanation of the emotionality in striving vs. post-striving experiences. In a 1976 essay, “Epicurus on the Art of Dying,” Miller discusses what he calls process pleasure (kinetic hēdonē) vs. state pleasure (katastematic hēdonē). Process pleasure, Miller says, is the pleasure in movement or process, fulfilling what one lacks and achieving one’s goals. State pleasure, by contrast, is the pleasure of established state or settled condition, being in a certain state of bodily health or equilibrium. State pleasure is experienced when one has reached statis, achieving one’s end and fulfilling one’s needs, while process pleasure is experienced when one is still actively employing some means in order to fulfill one’s needs.

As discussed in Part I, our association of pitch with the vertical dimension in physical space is not arbitrary, and we see now that experiencing upward moving pitch as embodying striving is not arbitrary, and neither is our association of major-minor harmony with generally positive, optimistic states of mind vs. generally negative, pessimistic states of mind.

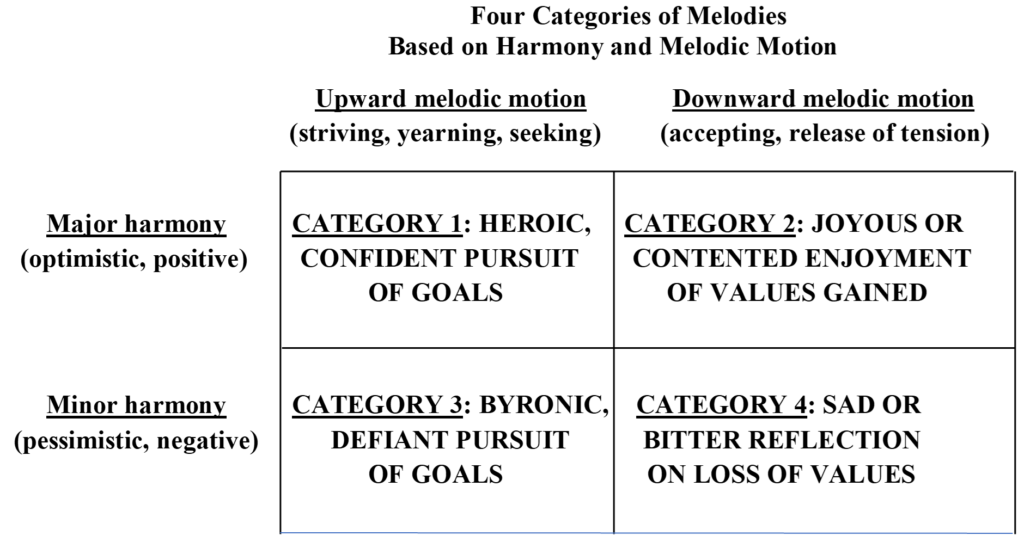

Putting two and two together, I am now going to state a principle of major importance to music aesthetics: the major-minor, success-failure factor explains why upward-directed melody is experienced as optimistic or pessimistic striving, and why downward-directed melody is experienced as a no-longer-striving mood that is positive or negative. Given the non-arbitrary basis of these two dimensions (Happiness and Striving, for brief), we can derive four distinct categories of melodies, based on their harmonic and melodic motion attributes: as shown here:

Then if we allow each category to be divided into instances that are more vigorous vs. less vigorous in their character, we get eight types of melodies. By labelling 1 and 2 as the major key melodies and 3 and 4 as the minor key melodies, and A as more vigorous and B as less vigorous, we can categorize them as follows:

- 1A: Exultant pursuit; 1B: Quiet confidence—generally, heroic or “benevolent.” An excellent example of both variants of Category 1 is “I’ve Gotta Be Me,” as recorded by Tony Bennett (exultant pursuit) and Sammy Davis, Jr. (quiet confidence), respectively. Since Davis’s recording was made first, I will discuss it first.

1B “I’ve Gotta Be Me,” Sammy Davis, Jr. (1968). (0:06-0:31). After an introduction, the melody rises from 0:06 to 0:31, then descends, and another climb begins at 0:36. The middle of the song begins with a different emotional character (1:06), but then returns to the basically heroic, upward motion (from 1:22). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BB0ndRzaz2o.

1A “I’ve Gotta Be Me,” Tony Bennett (1969). Similar comments apply to this version. https://youtu.be/VJvSKPoLZJw.

- 2A: Joyous celebration; 2B Serene happiness—celebratory or “eudaimonic.”

2B “My Heart at Thy Sweet Voice,” Gunnery Sgt. Sara Dell’Omo (2015). After an extended introduction, the main melody descends twice (0:06–0:36) in major harmony, expressing a serene, loving mood, before taking off in a series of very passionate, rising phrases. This is how you musically portray romance. (At least, it was 146 years ago!)

2A “Zing! Went the Strings of My Heart,” Frank Sinatra (1961). After a brief introduction, tempo picks up and the main melody (beginning at 0:39) consists mostly of descending phrases in major with small upward tails. (The middle of the song is a series of upward phrases.) It conveys celebratory excitement about a new relationship.

- 3A: Vigorous defiance; 3B: Stoic determination—gritty, “Byronic.”

3A the third movement of Beethoven’s Piano Sonata in C# Minor, op. 27, no. 2 (“The Moonlight”), performed by Valentina Lisitsa (2009). Listen at least from the beginning to 0:28. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zucBfXpCA6s. This may be the most violent, angry piece of music written up to then (1801). Some of my colleagues and friends say it doesn’t sound vigorously defiant. See what you think.

3B the first movement of Grieg’s Piano Concerto in A minor, op. 16, performed by Arthur Rubenstein (1975, at the age of 88!) and the London Symphony Orchestra. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I1Yoyz6_Los. After a dramatic introduction (mostly in Category 4A below), the main theme is by the orchestra (0:27–1:09) and then by the piano (1:10–1:52). In this case, the striving and yearning is more thoughtful and solemn, though still resolute and determined.

4A: Bitter anguish; 4B: Wistful mourning—tragic, “malevolent.”

4A the final movement of Tchaikovsky’s 6th Symphony (“Pathetique”) is anguish personified. It is not full-blown rage, but it is a very tortured movement with which to end a symphony, which most often is a triumphant ending to such multi-movement works. Listen from 35:28 onward (then listen to the entire symphony to hear it in context). https://youtu.be/GjACKNEI35E?t=2128.

4B “Blue Bossa,” Mary Juane Clair (2019). It is uncertain who wrote the lyrics (either in English or in other languages), but most listeners think they speak of loss and remembrance. These lyrics from the third verse get the message across: “The thought of how we met still lingers on. How can I forget that magic dawn? All the warm desire, the fire in your touch. The blueness of the trueness of our love.” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8_04AWfrMVg.

These emotional categories are discussed in Rand’s aesthetic writings in terms “sense of life.” (Especially see “Art and Sense of Life” and “What is Romanticism?” in The Romantic Manifesto.) We will not examine examples of them until Part III, because of the fact that melodies are almost always a combination of two or more emotional categories.

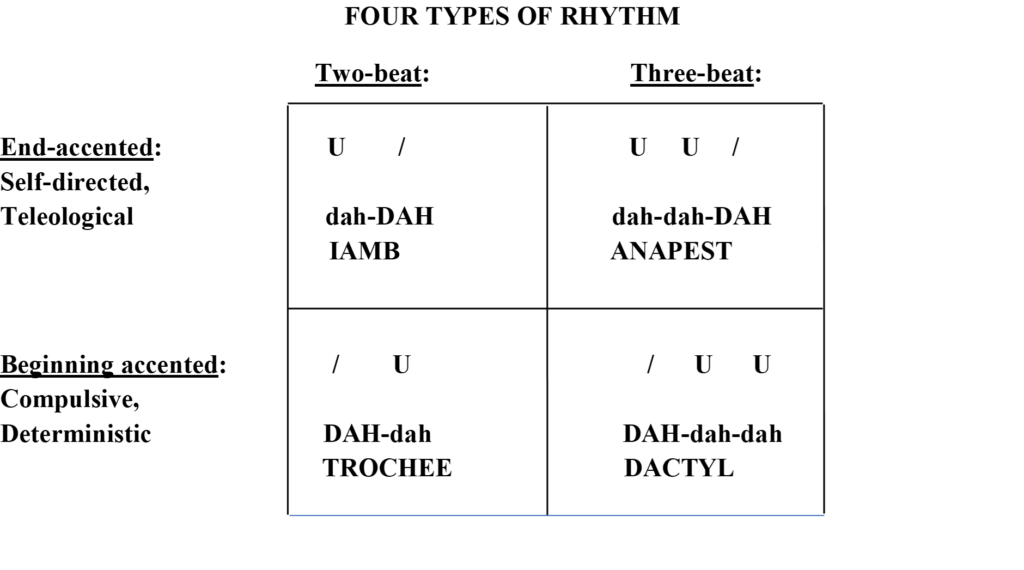

Finally, there is the very important issue of Pursuing Values vs. Being Driven, or Teleology[10] vs. Mechanism or, as I characterized it earlier, control—i.e., being in deliberate control of one’s actions, acting intentionally to achieve one’s chosen ends or “values” vs. being driven by inner or outer forces not directly in one’s control. In music, this issue relates to types of rhythm. This is probably the most controversial of the basic forms of embodying deep meaning in music. (Perhaps not accidentally because it’s my own idea!)

There are two basic kinds of rhythms (patterns of varied emphasis in a group of musical tones), and there are two variations of each, for a total of four. They each have a distinct meaning and accompanying emotional connotations and, I will argue, deep philosophical meaning. The two main types of rhythms are distinguished by whether a group of two or three notes is emphasized or “accented” on the first note or the last one—or, in technical terms, beginning-accented or end-accented.

The names for these different groups are borrowed from poetry, and the notes or words—technically, referred to as “beats”—in these patterns are either accented (emphasized) or not, as shown below by the upper-case and lower-case letters that illustrate the sound pattern in each of these rhythmic groups. (Say or think them quickly, in order to better get the feel of them.)

A two-beat end-accented group (or rhythmic figure) is known as an iamb, and the rhythm pattern sounds like dah-DAH (or tuh-DUMP).

An end-accented group of three beats is called an anapest, and the rhythm pattern sounds like dah-dah-DAH (or tuh-kuh-DUMP).

A two-beat beginning-accented group (or rhythmic figure) is known as a trochee, and the rhythm pattern sounds like DAH-dah.

A beginning-accented group of three beats is called a dactyl, and the rhythm pattern sounds like DAH-dah-dah.

Here are the four principal rhythms (or “feet,” as they are called in poetry). The accented beats are indicated with a hash mark and capital “DAH,” and the unaccented beats with a capital U and lower-case “dah”:

Now, you can call the following philosophical claim “Bissell’s Hypothesis” if you like—I’ve never seen it expressed anywhere else—but I attach deep philosophical significance and meaning to these rhythms. Specifically, I think that the two varieties of end-accented rhythms (the top row in the diagram) express pro-active, goal-directedness in music, while the two kinds of beginning-accented rhythms (the bottom row) express reactive, compulsive behavior.[11]

These rhythmic connotations are frequently encountered in music. I contend that they are well suited for expressing whether people can pursue and achieve values in the world in a purposeful manner, or instead are only able to helplessly react to forces beyond their control, whether frenzy, rage, despair, or some compulsive psychological state.

I further think, and the following examples will show, that if a given phrase or passage is even predominantly in one rhythmic pattern, the idea and emotion expressed will be apparent, though the mixing of patterns gives nuance, richness, and variety to the music. The same is even more so for melodic motion, which is almost never entirely in one direction.

As you listen to each example not just in the segment indicated, but in its entirety—at least, as I hope you do—you will probably notice that there are very few “pure” types either melodically or rhythmically among them. This is why I have to resort to snippets, and even then have two-beat and three-beat rhythms sprinkled among the ones exemplifying the other rhythm with the same position being accented.

A rare example of one-direction melodic motion—at least, on the phrase level—that everyone probably knows is Handel’s setting of James Watts’s hymn lyrics which became the traditional Christmas carol, “Joy to the World.” Here is a delightful performance by Pentatonix: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-Xo64Q2ucQ8.

The first four-measure phrase (0:29–0:33) is a full-octave, descending major scale set to the lyric “Joy to the world, the Lord is come,” with no reversal of melodic direction. If this doesn’t accurately connote realized pure joy, I don’t know what would!

Then the second phrase (0:33–0:38) ascends directly from the 5th to the octave on the words, “Let earth receive her King.” Again, a perfect marrying of melody and words to convey aspiration and purpose. Rhythmically, the first phrase has three beginning-accented rhythms, appropriate to a non-striving idea; and the second phrase has three end-accented rhythms which help to underscore the aspirational content of the upward melodic direction.

I could do an entire essay analyzing the emotional and philosophical meaning of the melodies of the traditional and popular Christmas carols, and I’m sure it would be interesting (if probably also controversial). For now, though, let’s consider some examples of how the four basic rhythmic patterns show up in popular and serious music:

Iambic: the two-beat, dah-DAH rhythm connotes heroic, assertive, or yearning moods, as in Lancelot’s “C’est Moi” in Camelot , “New York, New York” (a signature Frank Sinatra song), and Tony and Maria’s “Tonight” in West Side Story. Listen to these examples as you read below the lyrics showing the (predominantly) iambic pattern. (And please bear in mind that these are illustrations and interpretations of the meaning of the rhythm only and of these passages only. The melodic direction and harmonic mode have a meaning we will pass over; and other passages sometimes contain other rhythmic patterns with meanings distinct from those examined here.)

1. “C’est Moi” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j0BiJRI4GOE. (1:24–1:39) c’est MOI, c’est MOI, i’m FORCED to ad-MIT), ‘tis I, i HUM-bly re-PLY, that MOR-tal WHO these MAR-vels can DO, c’est MOI, c’est MOI, ‘tis I (11 iambs, 3 anapests, underscored)

2. “New York, New York” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=le1QF3uoQNg. (0:24–0:33) i WANT to BE a PART of IT, new YORK, new YORK (6 iambs)

3. “Tonight” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LkDJgEKNJZ8. (1:42–2:05) toNIGHT toNIGHT, it ALL beGAN toNIGHT, i SAW you AND the WORLD went aWAY, toNIGHT toNIGHT, there’s ON-ly YOU toNIGHT, what you ARE, what you DO, what you SAY (13 iambs, 4 anapests, underscored)

The iambic rhythm seems to have a natural basis in the sound of the human heartbeat. Listen to the introduction and the very ending of this performance by Frank Sinatra of Cole Porter’s “Night and Day.”

4. “Night and Day” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y3DFfUHty-w.

Anapest: the three-beat, dah-dah-DAH rhythm is also used to suggest heroism or assertiveness. Listen again to “C’est Moi,” linked above at (0:06–0:12) to hear cam-e-LOT, cam-e-LOT. Or persistent, seductive invitation, as in “Follow Me,” also from Camelot:

1. “Follow Me” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7zQQMQWWAiY. (0:03–0:37) through the CLOUDS, gray with YEARS, o-ver HILLS, wet with TEARS, to a WORLD young and FREE, we shall FLY, fol-low ME. a-pril GREEN, ev’-ry-WHERE, a-pril SONGS, al-ways THERE, come and HEAR, come and SEE, fol-low ME.

Or a passionately assertive appeal, as in “Come Back to Me,” by Sammy Davis Jr.:

2. “Come Back to Me” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QFw0ye4jJEE. (1:18–1:44) hear my VOICE, where you ARE, take a TRAIN, steal a CAR, hop a FREIGHT, grab a STAR, come BACK to ME, catch a PLANE, catch a BREEZE, on your HANDS, on your KNEES, swim or FLY, on-ly PLEASE, come BACK to ME. (12 anapests, 4 iambs, underscored)

The anapest rhythm is also used in more subtle ways, especially by Romantic composers like Sergei Rachmaninoff to create defiant or heroic energy and excitement in their accompaniment figures. Here are a piano example and an orchestral example transcribed for piano:

3. “Prelude in G Minor” (opening section) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SlcQWUn5DeI. (0:04–1:21)

4. “Piano Concerto No. 2 in C Minor” (third movement, solo piano arrangement) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mRevydYlk9s. (0:00 – 4:38)

The hint of horses’ hoofbeats in the above Rachmaninoff accompaniment figures is more explicitly suggested in a number of assertively heroic (or quasi-heroic) pieces, including:

5. The overture from the opera William Tell (aka “The Lone Ranger” theme) by Gioachino Rossini, as performed by the irrepressible Mnozil Brass. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NMyqdRKAL84. (predominantly anapest from 1:12 on, though you really must watch the entire video; it won’t kill you, unless you die laughing)

6. The overture from Franz von Suppé’s operetta The Light Cavalry, performed by the Mnozil Brass. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X34Ujm8FnMQ. (0:05 on)

7. The “Dudley Do-right Show” theme song by Fred Steiner. Here is a clip from the actual cartoon program: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Npfi0UZL2ow.

These examples are all intended to illustrate the teleological, purposeful, goal-directed character of end-accented rhythms and are echoed in nature by the heartbeat (iamb) and the hooves of swiftly running horses (anapest). By contrast, beginning-accented rhythms connote a kind of action that is not essentially teleological or goal-directed, but instead is more automatic and deterministic, more in the nature of an echo (or double echo), or perhaps the panting for breath (EXHALE-inhale, trochee) or the sound of a boxing speed bag (POCK-a-ta, dactyl).

Trochee: the two-beat, DAH-dah rhythm connotes a more mechanical process, a more physically focused and less goal-directed kind of compulsive, even obsessive motion.

1. The one vocal example of trochee included here is “La Vie en Rose,” a cabaret song from the early 1900s, sung by Andrea Bocelli (with recorded inserts by Edith Piaf). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4REbp0s_G9w. (0:40–1:16, 1:32–2:17, 2:34 to end) (Note: the middle of the song, sung twice at 1:16–1:32 and 2:17–2:34, is in the other beginning-accented rhythm, the dactyl)

2. A typical instrumental example of trochee is Johannes Brahms’s Hungarian Dance No. 1 in G Minor https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vHCTa1QNnso. (0:00–0:42)

3. Also, here is Johann Sebastian Bach’s deceptively calm Prelude in C Major: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=frxT2qB1POQ.

4. Another is Franz Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ALqOKq0M6ho. (6:00–8:30)

5. Yet another is Frederic Chopin’s frenetic Piano Etude op. 10, no. 4: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AEMgNMNeBr4. (0:00–1:56, listen for the steady pulses, and don’t be distracted by the incredibly fast figuration underlying the pulses)

6. “Flight of the Bumble Bee” as arranged for piano by Sergei Rachmaninoff. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M93qXQWaBdE. (entirety: same instructions as for the above Chopin piece)

7. One more: the final movement of Ludwig van Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No. 14 (“Moonlight”) in C# Minor: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XUzwdBQDzxw. (entirety; same instructions as for above Chopin piece)

Dactyl: the three-beat, DAH-dah-dah rhythm has a similar connotation to the trochee, as exemplified by dances like the tarantella, the hora (a Jewish celebratory dance), and even the noticeably less frenetic waltz. The hora and tarantella are frenzied, non-directed dances, aimed at expressing exuberance and blowing off steam (or spider venom).

1. “The World We Knew (Over and (Over).” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dthgRdTf0Ds.

2. “America.” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ogwR6L43KVw. (3:35 on)

3. “Stout Hearted Men.” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A_QUg_OYMfg. (0:51 – 1:43; hard to believe this is the same basic dactyl rhythm as in “America;” from 1:43 on, the rhythm is the two-beat trochee rhythm)

4. Liszt teamed up with Paganini for La Campanella: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H1Dvg2MxQn8. (14:00–18:35)

5. One of my favorite examples of dactyl is this performance by the incomparable Valentina Lisitsa of the middle section to Rachmaninoff’s Piano Prelude in C# Minor:

https://youtu.be/a22HqHrgIZk (1:24–1:55) (You may note that the dactyls come so quickly that they assume the function of individual “beats” and take on an alternating accented-unaccented or trochee rhythm when paired together, building on the impression of compulsive, irresistible motion established by the incredibly fast dactyl figures. This double layer of dactyl rhythm provides a very “impulse-driven” undercurrent that supports the powerful goal-directedness of the section. Also, note that, around 1:55, the trochee spreads out to a slower dactyl lasting to the end of the middle section at 2:04. In my more Randian moments, I think of this passage as “The Running of the John Galt Line.)

6. “The Minute Waltz” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3H0SRv8QNwk. Especially note the dactyl pattern in the left-hand accompaniment of the first and third sections (BOOM-chick-chick, 0:07–0:38 and 1:14 on). The melody is too rhythmically complex to analyze here, except I will point out that in the middle section (0:39–1:06), it employs an uneven (two-to-one duration ratio) trochee rhythm (DAH-dah) that maintains the driving beginning-accented character of the piece.

With this new distinction about rhythmic types amply illustrated, we can now formulate an even larger set of melodic types. Building on the foundation of the eight melodic types defined by melodic direction, harmonic mode, and level of vigor, we can add in another dimension characterized as placement-of-accent. Beginning-accented rhythms are deterministic, fatalistic, compulsive, obsessive, out of control, and end-accented rhythms are teleological, volitional, self-directed, deliberate, in control.

As noted in the examples above, the rhythmic meaning may arise independently of the melodic-harmonic meaning, but it can instead synergize with melodic-harmonic meaning in a very powerful, rousing manner. And that is just on the level of musical phrases. In either of these dimensions, the character of one phrase may be very similar to or quite different from the character of the next phrase.

Again, “Joy to the World” is a simple, easily understood example. Phrase 1 is expressive of pure settled joy of the coming of the King, while phrase 2 is aspirational of what must be done by everyone to “receive” the King. While the rhythm is almost entirely iambic, with the connotation of purposive, deliberate action (joy TO the WORLD the LORD is COME, let EARTH re-CEIVE her KING), the melody first descends in a settled, joyous phrase in the major key, and then it ascends in an aspiring, assertive phrase also in the major key.

Another example, “I’ve Gotta Be Me,” shows how alternating dactyl and trochee rhythms, both beginning-accented (WHETH-er i’m RIGHT or WHETH-er i’m WRONG… WHETH-er i FIND a PLACE in this WORLD or MERE-ly be-LONG), can combine together to reinforce the melody’s assertive, heroic upward motion and optimistic major harmony with a very insistent, deterministic drive, a feeling of “I can’t help it, I’ve got to do this.”

Beyond the complexities of these types of shifting nuance of meaning in the sequential unfolding of musical phrases, there are the even more profound complexities in the weaving together of similar or contrasting meanings in the simultaneous unfolding of different layers of musical structure, both melodically and rhythmically. The hierarchical layering of rhythms (discussed above in relation to Rachmaninoff’s G Minor piano prelude, along with the layering of melodic direction, is one of the chief sources of the richness and nuance of both serious music of the Romantic era and the best popular music from the 20th century. Much more will be said and illustrated about these complex, powerful attributes of music in Part III of this essay, as we delve even more deeply into the emotional and philosophical meaning of music.

To be continued in Part III: Ayn Rand and the Dialectics of Music

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

Notes

[1] This part of my essay is substantially revised from a presentation I made in July 2009 to a Free Minds Objectivist conference in Las Vegas, Nevada.

[2] See Bissell 2019. My interest in—indeed, deep appreciation of—the contributions of the African American musicians and songwriters is not limited to the powerful impetus they gave to jazz, country, and rock music. A crucial gift they gave to American popular music—something they didn’t invent, but instead persistently injected into the musical mainstream—was the rhythmic pattern known as “syncopation.” Although it is one of the traditional five rhythms derived from poetry—the rhythm known as “amphibrach”—I will postpone a discussion of it to Part III of this essay.

[3] For those wanting a widely multicultural introduction to music appreciation, I recommend White, Stuart, and Aviva’s Music in Our World: An Active Listening Approach (McGraw-Hill, 2001). Dr. Gary White was my music theory and composition instructor and mentor at Iowa State University, and at his invitation I authored a chapter in his textbook Instrumental Arranging (William C. Brown, Pub., 1992).

[4] The internet is rife with claims that “Emmanuel” Kant said: “music is the language of emotions,” which indicates that his 1790 Critique of Judgment may be the origin of this phrase. However, the alleged quote is never accompanied by a specific citation, and I have been unable to find anything remotely resembling such a statement in Kant’s writings.

[5] I grant that there may be some justification for regarding both process and object of music as being important to identifying the nature of meaning and emotion in music, in the same sense that both style and subject are aesthetically relevant in art, and both means and ends are ethically relevant in human action.

[6] Full disclosure: as indicated in Bissell 1998 and Bissell 2001, I do believe that Rand has the makings of a Grand Unifying Theory of process and structure in the dynamic arts, and I will have some comments on that idea in Part III of this essay. The work in these essays, however, is very much preliminary groundwork for such a theory and while perhaps startling in the amount of unfamiliar and challenging claims, will be far from a rigorous statement of the theory itself.

[7] In her essay “Art and Sense of Life” (1966), Rand draws a clear distinction between philosophical evaluation and aesthetic evaluation of art, and I basically follow her guidelines in applying this to the identification and evaluation of the emotional effectiveness of music.

[8] So, too, are the larger-scale structures and processes in literature and music—both the hierarchical layering or stacking of units of action and the goal-directed unfolding of progressions of such action. However, as already mentioned, in order to allow enough time for this essay to firmly establish how meaning functions on the simpler levels of musical motion and structure, plot-development in music will be discussed only relatively briefly, and the same will be true for the layering of melodic-rhythmic groupings. In Part III of this essay, some extended examples will more fully develop these larger-scale issues.

[9] For lay readers or those in need of a refresher, this article on the overtone series will be helpful, as will this video on major and minor chords. Especially listen (and look) at the portion from 03:58 onward.

[10] I mean “teleology” here not in the general sense of final causation—which means that, under given conditions, every action has a definite necessary result, determined by its nature, the nature of whatever it’s acting upon, and the nature of the given conditions—but in the sense of the narrower subcategory of goal-directed action, where an action of a living organism is directed by the internal “values” (preferences, whether biologically wired-in or chosen) of that entity toward a particular end or “value” (that which the organism acts to gain and/or keep, as per Ayn Rand’s definition). See my discussion in Bissell 2022, pp. 252–64 and 296–301.

[11] There is a fifth traditional rhythm that is a fusion of the end-accented iamb and the beginning-accented trochee, and it plays a very significant role in American popular music. I will discuss its philosophical and emotional significance along with a variety of examples in Part III of this essay.

References cited

Allysia Marie. 2015. “Major and Minor Chords: How to Figure Them Out Quickly, by Ear.” pianoTV (June 27). Online at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iWDaINpnNnc.

Atkinson, Sean. 2016. “Total Serialism.” YouTube (April 6). Online at: https://youtu.be/9C9ELx0Gr14.

Bissell, Roger E. 1998. “Kamhi and Torres on Meaning in Ayn Rand’s Esthetics.” Reason Papers 23 (Fall): 101–8.

______. 2001. “Critical Misinterpretations and Missed Opportunities: Errors and Omissions by Kamhi and Torres.” The Journal of Ayn Rand Studies 2, no. 2 (Spring): 299–310.

______. 2009. “Toward an Objective Aesthetics of Music.” Unpublished, presented to Free Minds conference, Las Vegas, Nevada, July 2009.

______. 2019. “Up from Oppression: Triumph and Tragedy in the Great American Songbook.” In Bissell, Sciabarra, and Younkins 2019, 203–231.

______. 2022. “Where There’s a Will, There’s a ‘Why’ Part 2: Implications of Value Determinism for the Objectivist Concepts of ‘Value,’ ‘Sacrifice,’ ‘Virtue,’ ‘Obligation,’ and ‘Responsibility.’” The Journal of Ayn Rand Studies 22, no. 2 (December): 251–317.

Bissell, Roger E., Chris Matthew Sciabarra, and Edward W. Younkins. 2019. The Dialectics of Liberty: Exploring the Context of Human Freedom. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books.

Cooke, Deryck. 1959. The Language of Music. Oxford University Press.

James, Mark. 2022. “What is Aleatoric Music? With 7 Top Examples and History.” Music Industry How To (December 15). Online at: https://www.musicindustryhowto.com/what-is-aleatoric-music/.

Kant, Immanuel. [1790] 2002. The Critique of the Power of Judgment. Rev. edition. Trans. Paul Guyer. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Lippman, Edward Arthur. 1952. “Music and Space: A Study in the Philosophy of Music.” Ph.D. dissertation, Columbia University. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University Microfilms.

Meyer, Leonard B. 1989. Style and Music: Theory, History, and Ideology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Miller, Fred D., Jr. 1976. “Epicurus on the Art of Dying.” Southern Journal of Philosophy 14, no. 2: 169–77.

n.a. 2023. Harmonic series (music). Wikipedia (September 20). Online at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harmonic_series_(music).

Peikoff, Leonard S. 1997. “The Survival Value of Great, though Philosophically False, Art.” Audio lecture. Online at: https://courses.aynrand.org/campus-courses/the-value-of-great-though-philosophically-false-art/the-survival-value-of-great-though-philosophically-false-art/.

Rand, Ayn. [1936] 1959. We the Living. New York: Macmillan (1st ed.), Random House (2nd ed.).

______. 1943. The Fountainhead. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill.

______. 1957. Atlas Shrugged. New York: Random House.

______. 1964. The Virtue of Selfishness: A New Concept of Egoism. New York: New American Library.

______. 1966. “Art and Sense of Life.” In The Romantic Manifesto. 1975, 34–44.

______. 1969. “What is Romanticism?” In The Romantic Manifesto. 1975, 99–122.

______. 1971. “Art and Cognition.” In The Romantic Manifesto. 1975, 45–79.

______. 1975. The Romantic Manifesto: A Theory of Literature. 2nd revised edition. New York: New American Library.

Storr, Anthony. 1992. Music and the Brain. New York: The Free Press.

von Helmholtz, Hermann Ludwig Ferdinand. 1950. On the Sensations of Tone as a Physiological Basis for the Theory of Music. First and fourth German editions: 1863, 1877, respectively. New York: Dover.

White, Gary. 1992. Instrumental Arranging. Dubuque, Iowa: William C. Brown Publishers.

White, Gary, David Stuart, and Elyn Aiva. 2001. Music in Our World: An Active-Listening Approach. New York: McGraw-Hill Higher Education.

Musical pieces analyzed

Bach, Johann Sebastian. Prelude in C Major (1742)

Beethoven, Ludwig van. Piano Sonata No. 14 (“Moonlight”) (1801)

Bernstein, Leonard (music), Stephen Sondheim (lyrics). “Tonight” and “America” (West Side Story, 1957, musical; 1961 and 2021, film)

Brahms, Johannes. Hungarian Dance No. 1 (1879)

Chopin, Frédéric. Piano Etude Op. 10, No. 4 (“The Torrent”) (1830), Waltz in D-flat Major Op. 64, No. 1 (“Minute Waltz”) (1847)

Dorham, Kenny. “Blue Bossa” (1963, bossa nova jazz song).

Guglielmi, Louis, aka “Louiguy” (music), Edith Piaf (lyrics). “La Vie En Rose” (1947)

Hanley, James F. “Zing! Went the Strings of My Heart” (Thumbs Up! musical revue, 1935)

Kaempfert, Bert (music), Carl Sigman (lyrics). “The World We Knew (Over and Over)” (1967).

Kander, John (music), Fred Ebb (lyrics). “New York, New York.” (New York, New York, film, 1977)

Lane, Burton (music), Alan Jay Lerner (lyrics). “Come Back to Me.” (On a Clear Day You Can See Forever, musical, 1965)

Lizst, Franz. Hungarian Rhapsody in C-sharp Minor no. 2 (1857); Grandes études de Paganini no. 3 (“La Campanella”) (1851)

Loewe, Frederick (music), Alan Jay Lerner (lyrics). “C’est Moi” and “Follow Me” (Camelot, 1960, musical; 1967, film)

Marks, Walter. “I’ve Gotta Be Me” (1967, Golden Rainbow, musical)

Porter, Cole. “Night and Day” (1932, Gay Divorce, musical; 1934, The Gay Divorcee, film)

Rachmaninoff, Sergei. Prelude in C# Minor (1892), Prelude in G Minor (1901), 2nd Piano Concerto (1901). Also, he did a piano arrangement (examined herein) of Rimsky-Korsakov’s “Flight of the Bumble Bee.”

Rimsky-Korsakov, Nikolai. “Flight of the Bumble Bee” (1900, The Tale of Tsar Saltan, opera)

Rodgers, Richard (music), Oscar Hammerstein (lyrics). “Do-Re-Mi” (The Sound of Music, 1959, musical; 1965, film)

Romberg, Sigmund (music), Oscar Hammerstein (lyrics). “Stout Hearted Men” (The New Moon, 1927, film)

Rossini, Gioachino. William Tell Overture (William Tell, 1829)

Steiner, Fred. “Dudley Do-Right” theme (Dudley Do-Right of the Mounties, cartoon program, 1959)

Tchaikovsky, Pyotr Ilyich. Symphony No. 6 in B Minor (“Pathetique,” 1893)

von Suppé, Franz. Light Cavalry Overture (Light Cavalry, 1866)