Translating deep thinking into common sense

Transcript: Brian Doherty Interviewed on The Savvy Street Show

By The Savvy Street Show

April 28, 2024

SUBSCRIBE TO SAVVY STREET (It's Free)

Transcript: Brian Doherty Interviewed on The Savvy Street Show

Date of recording: April 17, 2024, The Savvy Street Show

Hosts: Roger Bissell and Marco den Ouden. Guest: Brian Doherty.

For those who prefer to watch the video, it is here.

Editor’s Note: The Savvy Street Show’s AI-generated transcripts are edited for removal of repetitions and pause terms, and for grammar and clarity. Explanatory references are added in parentheses. Material edits are advised to the reader as edits [in square brackets].

Roger Bissell

Welcome back to the Savvy Street Show, everyone. Good evening. Hello, my name is Roger Bissell and I’m standing in here for our regular host, Vinay Kolhatkar, who is off on another assignment, as they say. As usual, we have a distinguished guest whom you will meet in just a moment. Some of you are subscribers and may already be acquainted with my co-host, Marco den Ouden. Marco is a well-known libertarian and publisher of the blog, The Jolly Libertarian. And he does not travel all around the world on Christmas Eve delivering presents. That’s a different jolly person. But Marco is going to introduce our special guest tonight. So welcome to the show, Marco.

Marco den Ouden

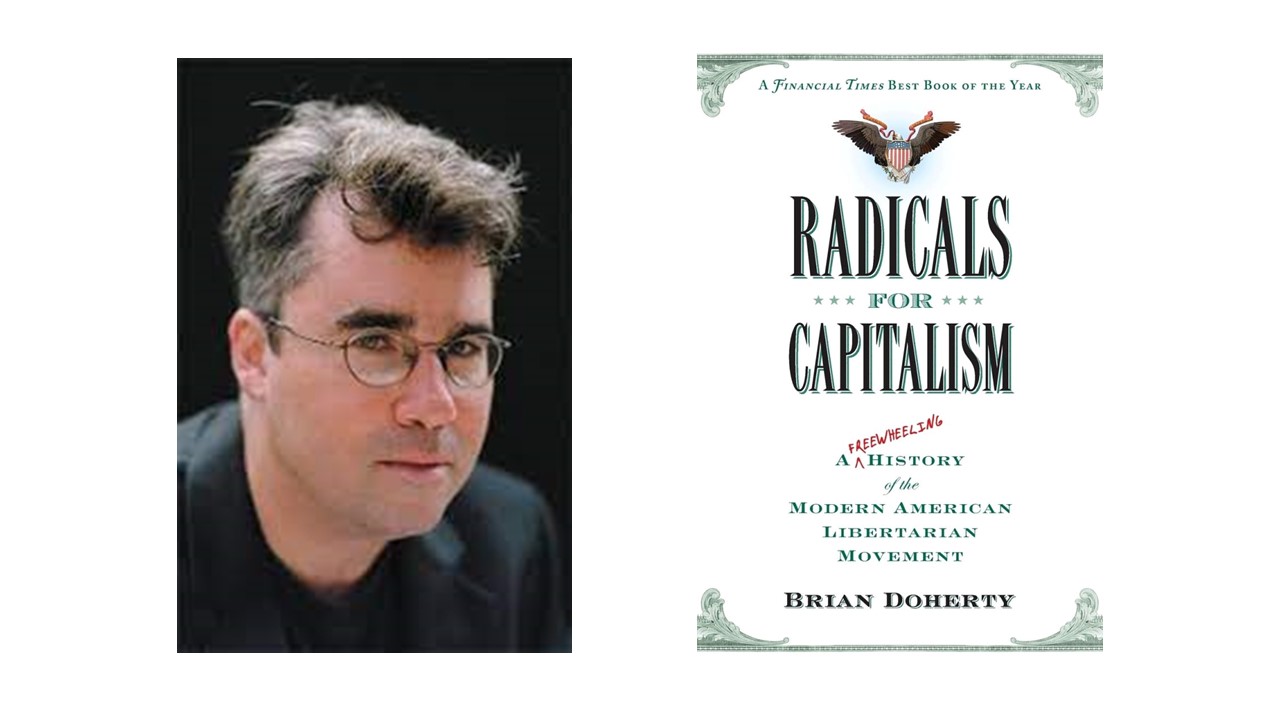

Thank you, Roger. Our guest today is Brian Doherty, a senior editor at Reason magazine. https://www.thesavvystreet.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/BD-160×65.jpg His work’s been published in over a hundred publications, including the Washington Post, the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, Mother Jones, and Wired. He’s the author of five books. Two of them, This is Burning Man and Dirty Pictures, are on pop culture, and the rest are on libertarian themes, and we’re going to be discussing one of his books today, Radicals for Capitalism: A Freewheeling History of the Modern Libertarian Movement. I’ve got a copy of it here. It’s an excellent book, 600 pages of dynamite. And if you’ve never read it, I highly recommend it. One of the things I really loved about your book was that I discovered libertarianism in 1969 when I read Capitalism, the Unknown Ideal. I listened to the Branden lectures on vinyl, and I was an early subscriber to magazines like The Rational Individualist and Reason. I was there in the heyday of the beginning of the modern libertarian movement. So it brought back a lot of memories. Was that really the launch of the modern libertarian movement around the late ’60s, early ’70s? The popularization of libertarian ideas that had been under the radar in the mainstream for many years?

Brian Doherty

That is a very interesting question, where this story should start. If people choose to read Radicals for Capitalism, which I hope they do, they will see that while obviously the ideas of liberty are at the root of Western civilization itself, you can find some of it in the Bible, you can find it in the Lao Tzu, you can find it in the Enlightenment, you can certainly find it in the American founding, I wasn’t telling the whole history of the idea of liberty, which is a far bigger topic than even a book as big as Radicals for Capitalism could do. I was trying to tell the story of a particular and specific group of intellectuals and organizations in America—the word “American” is in the subtitle of the book—that pushed the ideas of liberty to their most radical edges.

I made the decision, and if you read the book you can decide whether you think I’m right or not, that a good place to mark that beginning was with the founding in 1946 of an organization called the Foundation for Economic Education by a man named Leonard Read [pronounced “reed”]. We’re going to get to talking a bit deeper about Leonard Read later. So, that was the first organization that was dedicated to the promotion of what I defined as modern libertarian ideas, particularly the economic end of it, obviously in the very name of the organization, Foundation for Economic Education. Leonard Read believed that one of the problems with America in the post-war, post-New Deal era was that Americans did not properly understand the truths of free market economics as taught most particularly by great libertarian founding fathers such as Ludwig von Mises and Friedrich Hayek.

Every libertarian thinker had their vision of how a free-market economy should work shaped by Ludwig von Mises.

Ludwig von Mises in many ways is what you’d call the fountainhead of all of this, because nearly every libertarian thinker who followed von Mises had their vision of how a free-market economy should work shaped by Mises, including Ayn Rand, who you started with.

Ayn Rand, of course, much more than Mises, was the great popular exponent of radical libertarian ideas in the sense that she was not just an economist, writing economic tomes read only by economists, but she was a popular novelist, a massively popular novelist, despite pushing a set of ideas that nearly every modern liberal (as distinct from the classical liberals of the libertarian movement) set their teeth on edge.

Ayn Rand was the great popular exponent of radical libertarian ideas.

I mean, anyone who’s a fan of Ayn Rand has encountered, to either their amusement or their regret, the deep level of angry hatred that Ayn Rand can inspire in people. And it’s very unfair, obviously, because Ayn Rand’s message was the most humane humanitarian message anyone could imagine delivering, was saying that you owned yourself and you had the right to live for your own happiness, that you ought not do anything to harm other people’s life or property. I mean, what could be a better message than that? But she was very hated for it. So what Rand did, and particularly as you just mentioned, with the Nathaniel Branden Institute, people might be wondering why, how is the name Nathaniel Branden getting in this if we’re talking about Ayn Rand. If you don’t know the story, and my book tells you the whole story, Nathaniel Branden was for a while Ayn Rand’s right-hand man, and they actually had a romantic affair, which is a sordidly fascinating tale that my book gets into that we probably don’t need to get into too deeply here, but Nathaniel Branden helped convince Ayn Rand at a time when she was very depressed that she had written these massively successful novels, The Fountainhead published in 1943 and Atlas Shrugged in 1957. Atlas Shrugged, even more importantly, was the book that really explained everything about her philosophy of life, her philosophy of reason, her philosophy of politics, all in a brain-blastingly tense and great thriller novel, essentially, certainly the greatest philosophical thriller ever written, and it still sells hundreds of thousands of copies to this day. But Rand was a little depressed that she felt she had laid it all out in Atlas Shrugged, and any reasonable, decent person would become aware that this book existed, read it, and become a free-market libertarian Objectivist, but that didn’t happen. I mean, the book was very successful, but it did not turn the culture in the direction that she wanted it turned, and she was a little depressed about that.

Nathaniel Branden, who was a young fan of hers, convinced her, “Hey, you can’t just write these novels and expect people to come to you. A lot of people aren’t actually going to see the philosophy inside the fiction.” I think any fan of Rand is aware that that happens. All the time to this day, I run into people who are like, “Oh gosh, yeah, The Fountainhead, Atlas Shrugged, love them, love those novels,” and yet some of them might be complete commies. Somehow her skill as a novelist allowed her to win fans of her as a novelist who weren’t necessarily intelligent or aware enough to get the philosophy. So Branden [told Rand] you need to actually boil down the philosophy and create an organization, which—a little bit nervy on his part, honestly, I think, but Ayn Rand let him do it—he called this Institute that was pushing Ayn Rand’s Objectivist philosophy the Nathaniel Branden Institute. And as you were just mentioning, there were both meetings across the country where people would get together and talk about this stuff or listen to the vinyl LPs of the lectures of Branden, Rand, and certain of Rand’s most trusted associates explaining Objectivist aesthetics, explaining Objectivist politics, explaining Objectivist economics. So that was about the first time that libertarian ideas actually created an excuse for groups of people to gather together self-consciously. The Foundation for Economic Education was an organization that mailed you pamphlets or magazines. It wasn’t necessarily a structure to gather in fellowship.

The whole Ayn Rand scene and the Nathaniel Branden Institute created the first opportunity for libertarians to actually gather in fellowship.

So, for sure, in the late ’60s, the whole Ayn Rand scene and the Nathaniel Branden Institute scene created the first opportunity for libertarians to actually gather in fellowship, and that had a lot of repercussions moving down the line.

One thing I want to add to that before we move on is: simultaneously and involving a lot of people who were fans of Ayn Rand, there was sort of a college movement, some of it centered in the conservative youth organization, Young Americans for Freedom, who had their more libertarian wing, who in 1969 openly schismed with the more right-wing Young Americans for Freedom, some of it over the issue of draft resistance. The libertarians were like, yeah, we need to actively resist the draft. The conservatives didn’t necessarily agree with that. And that led to a bunch of student organizations, like Students for Individual Liberty, and eventually in 1972 the political party called the Libertarian Party, which has been a big part of it.

Roger Bissell

Sure. And thanks for that overview of the early days of the movement. Now, the publication date of your book, was it about 2007? Do I have that right or am I in the ballpark?

Brian Doherty

That’s exactly right.

Roger Bissell

Okay, so from 1957 of Atlas Shrugged to 2007, that’s 50 years. That’s not just a hop, skip, and jump. In the meantime, a lot of liberty went down the river, I guess. Was your book, was it like, did somebody put a bug in your ear or was it just something you just jumped in and said, well, I’ve got to do this? What kind of support did you get from individuals and organizations in your research and the publishing and so on? Just give us a little bit of behind-the-scenes on that.

Brian Doherty

Sure. The important thing about there being a movement—I mean, the ideas exist. You can have books like Ayn Rand’s and Ludwig von Mises’s and Murray Rothbard’s, and people can read the books, and it’s going to effect change in their minds—but it’s important, as I just said, Ayn Rand was convinced of this by Nathaniel Branden; Murray Rothbard believed this from the beginning, that you needed to create a structure. The word “movement”—I think we all kind of understand what it means, but I’ll dig into it a little pedantically—it’s groups of people and organizations that are dedicated both to promoting the ideas and to helping the other people who promote the ideas.

A movement – it’s groups of people dedicated to promoting the ideas and helping other people who promote the ideas.

So I got the idea to write this book when I was an intern at the Cato Institute.

The Cato Institute is a big part of the story. It was founded in 1977 by the petrochemical billionaire Charles Koch and a former investment advisor named Ed Crane because they thought there needed to be a think tank that differed from FEE, I talked about the Foundation for Economic Education earlier, FEE tried to stay very abstract, only be about ideas. They didn’t tend to be about politics, campaigns, or even specific legislation. Cato was meant to be an organization, the kind of place that would have an op-ed in the Washington Post discussing this candidate or this particular law that was being proposed, a more active, and in the scrum of actual politics, libertarian think tank. So that existed since ’77, and it was there for a young, immediately post-college libertarian like me to get an internship and eventually a job. I met a fellow intern there, a guy named Chris Whitten, and in just the kind of after-hours bull session that young impassioned political radicals get into, we started talking about what we knew and understood about movement history. We realized it wasn’t necessarily a heck of a lot, and where could we go to learn more? Not to brag too much, but I guess maybe even at that point, I’d been reading enough magazines and talking to enough people that maybe I knew a little more about it at that stage already than Chris or anyone else in the room did. So Chris said, “Oh, well, maybe there should be a book in this, and maybe you should write it,” and I thought that was a pretty good idea.

On the internet now, thanks to organizations like Cato and the Mises Institute, you can find libertarian articles and even entire libertarian books.

Chris helped connect me to a woman not with us any longer named Andrea Rich, a very important figure in the spread of libertarian ideas from the ’80s on. She for many years ran an organization that old timers might remember called Laissez Faire Books, and this is pre-internet. On the internet now, especially thanks to the work of organizations like Cato and the Ludwig von Mises Institute, you can find all these libertarian articles and even entire libertarian books. You just find them at your desk online. Back in the ’80s and ’90s and ’70s, that was not the case. Books were rare and hard to find, especially libertarian books, which tended not to have enormously large press runs if they weren’t by Ayn Rand or Milton Friedman. So, Laissez Faire Books—and this was pre-Amazon, you’ve got to remember—they dedicated themselves to being a seller of books about liberty. They had a guy named Roy Childs, who was a great autodidact libertarian mind, and he edited their newsletter for a while. He was responsible for finding good libertarian books, writing great descriptions of them, and they would sell them by mail, mail order catalog. Roy tragically died very young in 1992, and I never met him, but everyone who had met and worked with him had a lot of love and affection for him, Andrea, among them; Andrea was the owner/boss of Laissez Faire Books, and Roy Childs was the mind and the writer of it.

So, Andrea in Roy’s memory started a fund for support of independent scholars called the Roy Childs Independent Scholars Fund; and through that, after I convinced her that I had a handle on the topic and could do a good job with it, she helped me—over the course of, I must admit, the 12 years it took me from the time I started the project to the time it was published—with things like, if I needed a libertarian book, she would help me pay for it; if I needed to travel to an archive, she would help pay for it; if I needed to travel to interview people, she helped pay for it. So she subsidized the travel, subsidized the book buying, subsidized the research trips with great patience over many years. And then, of course, since we’re market intellectuals, she was like, “I expect you to find a normal, respectable publisher for this book. I don’t want to have to publish it myself, you know?” I was fortunate enough to find a very normal publisher, a publisher who did not have any special love or affection for the ideas of liberty. That had its pluses and minuses, but to me, the big plus was that I was able to convince this publishing house called Public Affairs. They still exist, and if anyone goes to Public Affairs’ catalog, they will see it’s kind of weird that this house published this positive book about libertarianism, and it was. I don’t think it was about tooting my own horn or the quality of my own work—a little bit, maybe—but I think that the libertarian movement had succeeded enough by 2006 when I sold the book that any kind of publisher of political books, whether they believed in this stuff or not, whether they thought libertarianism was right or not, whether they thought libertarianism was a good idea, they recognized libertarianism is a very important part of the American political landscape, and an educated American watcher of politics needs to understand it, and they agreed to [publish] the book.

There’s a very funny, telling anecdote I want to share to wrap up this part of it, which I think is a sign of how not-respected libertarian ideas were in certain areas of the American intelligentsia. The year that I sold the book, I was at the wedding of a friend who was a Washington D.C.-based political writer, not herself a libertarian. Most of the guests at the wedding were not libertarians. I was talking to a fellow wedding guest who I think worked for one of the university presses in the Midwest, and you have the, “Oh, what are you doing? What do you do?” And I mentioned I was all excited, “Oh, I just sold my proposal to write a history of the American libertarian movement.” And she had already figured out that, “Oh, but you are a libertarian.” And she actually had the nerve to say to me, “Oh, well, do you think it’s appropriate that you who actually believes all this crazy stuff should be the person writing a book about it?” Obviously that is not a standard that she would apply to any other, she wouldn’t say that “Oh, if you’re writing history of the American civil rights movement, you shouldn’t believe in it,” right? I mean, that’d be a crazy thing to say, but her opinion of libertarianism was so low that she thought there was something untoward about someone who actually believed in it writing a book about it. But I, of course, maintain that it was, obviously, if you read this book and you hate libertarian ideas, you can read it through that filter, but I would maintain that my ability to understand it and explain all this stuff was very much helped by the fact that I actually thought it was all mostly correct as well.

Roger Bissell

Oh, how egocentric of her to believe that anything that she disapproves of should only be written about by a critic of that thing. Oh, man.

Brian Doherty

Exactly.

Marco den Ouden

Yes, indeed. Brian, you mentioned already Leonard Read, and The Freeman was another one of the magazines that I subscribed to in the early 1970s. And I was surprised to read in your book about the role that Read played in the early movement. Can you talk a bit about those early days and Read’s influence in the libertarian movement?

Brian Doherty

You bet. So yes, he launched FEE in—I’m just going to call it FEE, which stands for Foundation for Economic Education, it’s faster to say FEE—in 1946 at a time when the ideas of free markets and liberty were at a very low ebb. We had decades of the New Deal, decades of a war economy, everyone who was anyone believed that state control of the economy was the only thing that was saving us from a depression, and state control of the economy was necessary for big endeavors like fighting a war, right? And F. A. Hayek in 1944 had written his very important book, The Road to Serfdom, which tried to make people see—he wrote it during World War II, but it kind of had its biggest impact in the years after World War II—to show people that the things that we hated about Nazi Germany and the things that we are nervous about even our ally during World War II, the Soviet Union, those things, that kind of state control of the economy, Rooseveltism and New Dealism is (and I’m oversimplifying a little bit) like a mild version of that. It’s that same idea, that the state is more important than the individual, that the state has more knowledge about how to manage the economy, the state has more knowledge about how to manage your life. And he tried to explain that we, if we stuck on the sort of New Deal path, it was just taking us down the same road that the Nazis and the Soviet communists had already done. And this was a bad idea.

Leonard Read was appalled that many American businessmen didn’t understand the importance of private property and free markets.

Now, Leonard Read was an ex-Chamber of Commerce guy. He had just been a staffer of the American Chamber of Commerce. He was a staffer for a while with an organization called the National Industrial Conference Board. He was sort of a guy who stood for the interests of American business, and it appalled him that even many American businessmen and industrialists in that wartime didn’t understand the importance of private property and free markets, which Read had learned about from von Mises and Hayek. He felt that organizations like the Chamber and organizations like the National Association of Manufacturers were seen by some people as organizations that stand up for businesses’ interests. He thought that we don’t want an organization that stands up for the interests of business per se, because the interest of business in the controlled economy can be, “Okay, how can we get the tariffs that are going harm our competitors? How can we get the regulations that are going to stymie the small businesses more than they stymie us?” He realized that it wasn’t about pro-business, it was about pro-liberty, it was about pro-private property, it was about pro-free markets. So he started this organization to promote those ideas, and he published and distributed literature by von Mises and Milton Friedman and Hayek. You could pay for FEE’s literature, but he also gave it away for many, many decades. Anyone who asked to receive The Freeman, their monthly publication, would receive it.

Leonard was a very homey and folksy guy. He was not highfalutin’. He had a very good way to sell the ideas of liberty with homey, folksy metaphors that really appealed to small businessmen. At the time, it was an era of the small, family-owned business. He definitely appealed to those guys. He was probably not a great guy for the era of mass bureaucracy, but he was a guy who one-on-one could even—and I tell a lot of stories like this specifically in my book—he could get some angry union guy to write a letter to him, very mad that Leonard Read didn’t approve, say, of the union’s power to shut down a company if they wanted to go on strike, which, of course, Leonard Read did not approve of. Leonard would just calmly explain the principles of liberty, the principle of private property, the principle that surely anyone should be able to choose to work for whoever he wants, and you as a union man may decide, “I think my wage is too low and I’m going to withhold my labor until I get the wage I want. Sure, that’s your right, but it’s not your right to forcibly stop someone who is willing to take that wage, right?” And he was very frequently able to turn even enemies of liberty into fans of it. And from a very early start with FEE, he was able to gather, you know, a million. And it’s like that joke from Austin Powers: a million dollars doesn’t sound that impressive, but in 1946, it was very impressive that he was able to gather a million dollars from people who knew and trusted him. He was able to do this year after year to be the guy who spread these ideas. Through most of the 1950s, if you were an academic or a polemicist or a writer who wanted to write about liberty, FEE was almost the only game in town, like many of the great minds of the libertarian movement from Baldy Harper who went on to found the Institute for Humane Studies, which is still around, that sort of specializes in teaching students and academics in the cause of liberty; Murray Rothbard, who I think we’re going to get to in a little bit, he went through FEE. FEE was the main distributor of Frederic Bastiat, the great 19th century classical liberal economist and ferocious foe of protectionism; and the great promoter of Henry Hazlitt, who wrote the book Economics in One Lesson, which Leonard Read and I both agreed is maybe the very first book anyone should read to understand the free-market perspective.

So Leonard kind of stood alone and he stood proud and he kept these ideas alive in a time when almost no one believed them. And FEE is still around. It’s not quite the same as it used to be. I never met Leonard Read, but I read his diaries, I read his letters, I talked to many, many people who met him and who were turned around by him. He was a guy who apparently had an almost magic and rare sort of charisma. If you got in a room with him and he told you what was what, you were apt to believe it. Of course, it didn’t hurt that he was pushing a set of ideas that actually were just and correct. So yes, Leonard Read is certainly a character who ought not be forgotten in the history of American libertarianism.

Marco den Ouden

Yes, a very interesting character indeed. I think probably his most famous writing is “I, Pencil,” which is still very popular today. And he also played a role in having Ayn Rand’s Anthem brought to publication in North America. And speaking of Ayn Rand, going back a few years before Read, 1943 was a pivotal year in the movement with the publication of three books by three female writers who are described as “the three furies of libertarianism.” Can you give us a brief overview of these remarkable women and their contribution to libertarianism?

Brian Doherty

You bet. You know, Ayn Rand is one of them, and we all know Ayn Rand. I hope, I mean, I think almost everyone in America at least is aware of the name of Ayn Rand, whether they understand her or not. We all know Ayn Rand. But the other two, who were both friends of Rand and influences on Rand, and Ayn Rand was not a woman who was too fond of admitting to any influences other than Aristotle, but even she, if you read her collected letters, admitted that she was helped to understand things about liberty by these two friends of hers. Very similar women: one was named Rose Wilder Lane; one was named Isabel Patterson. I can talk about them as a pair because they had a lot in common. They had some distinctions, too, which I’ll get to before I’m done, but they both grew up on the American frontier in the early decades of the 20th century. Rose Wilder Lane, very famously so, because Rose Wilder Lane was the daughter of Laura Ingalls Wilder, who most Americans know as the author of what are called The Little House on the Prairie books, which is her mother’s account of essentially her childhood, growing up on the American frontier. And we don’t need to get too deeply into this here, but one of Rose Wilder Lane’s contested claims to fame, as many people believe, and I get into this deeply in my book, is that Rose Wilder Lane, who was herself a successful novelist, functioned as almost a ghostwriter of sorts for her mother—that in a sense, Rose Wilder Lane should be credited with the great achievements of Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House books, which of course have been a great influence on generations of American children, imbuing them with, if not a hardcore libertarianism, certainly a sense of the necessity of hard work, the necessity of private property, and the use of private property for individuals and families to thrive.

Both Lane and Isabel Patterson had that kind of background. Both of them in the same year, 1943—the year that Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead came out, and The Fountainhead, of course, is a novel with a sort of libertarian spirit behind it—Lane and Patterson both wrote books of nonfiction in that year that really…you can go back and read them now, and everything that we understand about the ideas and the mentality and even the tone of everyone who’s called themselves a libertarian since then can be found in these books. It’s kind of extraordinary. I’m actually going to quote a little bit from Isabel Patterson’s biographer, Stephen Cox, because he explained this very well. He was summing up what Isabel Patterson’s book with the curious title, The God of the Machine…I’ll very quickly explain that. She had the metaphor of the free human spirit as the thing that animates the machine of technological culture that keeps us all rich. It’s a little more complicated than that, but that’s why her book is called The God of the Machine. Anyway, Cox summed up the message of that book, and it also applies to Rose Wilder Lane’s book called The Discovery of Freedom, that they were pushing, to quote Cox, “a belief in absolute individual rights and minimal, not just limited, government, an advocacy of laissez-faire capitalism, and an individualist and subjectivist approach to economic theory,” which is known as the Austrian approach to economics after Mises and Hayek, who were the greatest exponents of it. Back to Cox: Patterson and Lane were dedicated to “opposition to social planning, victimless crime legislation, and any form of class or status society.”

No other American political philosophical movement has as staunch and solid a feminist background as libertarianism does.

Now, neither of their books…Ayn Rand’s book was a bestseller, but Patterson’s and Lane’s books did not sell a lot at the time. As we had alluded to earlier, 1943 was not a great time to find a ready audience, ready to hear a hardcore libertarian message. Everyone just had their head buried in Roosevelt and the New Deal at that time. So it slightly discouraged both Lane and Patterson, and they didn’t do a lot of work after that. Neither one of them accepted Social Security later on in life. Rose Wilder Lane famously said that true social security was your own land and a basement full of canned goods. True social security was individual self-sufficiency. Great minds…they should be feminist heroes, right? Because they were women fighting against the grain, doing important social and philosophical work against great odds in a man’s world. But, of course, since modern feminism tends to lean, if not be very dominated, by leftist, anti-individualist, anti-capitalist thinking, unfortunately, none of these women are seen as the feminist heroes that they should be. But, you know, if anyone hits you with that cliche about libertarianism, that it’s a club for boys in their basements, it’s worth reminding them that everything about the ideas of libertarianism can be found in these three books by these three women that came out in the same year, 1943. It’s not something that I think any other American political philosophical movement can say. None of them have as staunch and solid a feminist background as libertarianism does.

Roger Bissell

Well, that was very interesting. I enjoyed particularly hearing about your comparison between Isabel Patterson and Rose Wilder Lane. Rose Wilder Lane, I think, had some kind of business or media connection with Roger Lea McBride, who was the very second Libertarian Party presidential candidate [in 1976], and I remember he had a campaign button that said, “Roger who?”, and I got one of those because of my name, of course. I love it, and I still have it. I entered college as a conservative Republican, and then I helped form a conservative group and it was affiliated with the Young Americans for Freedom. And then I read Ayn Rand’s essay where she pretty much wrote a requiem on the conservative movement and said, “We are not conservatives. We are ‘radicals for capitalism.’” And I thought, oh, that is a phrase for the ages. And I said, yes, I’m not a conservative either. I am one of those. And then shortly after that, I realized, oh, I’m a libertarian. I started hearing about them. And so, it’s been over 50 years now. And I just wonder in your view, just looking now over the last 17 years since you wrote your book, how do you view the influence of the libertarian movement? Do you think it has gotten better or fallen off or is just kind of holding its own? Is it an idea that’s more relevant than ever, or are we losing the intellectual battle? How do you see that?

Brian Doherty

There’s an optimistic and a pessimistic way to look at this. I’m certainly going to start off with the optimistic because I think that that’s better for the soul and better for the morale, and I think there’s a lot of truth to it, and I’ll explain why.

I think the movement has done amazing things since I wrote the book, and I’m going to have to say here the name Ron Paul, who I know is controversial with some, but I think it’s the touchstone that helps explain this. This book came out in 2007, and I mentioned Ron Paul in it because he was this kind of interesting anomaly at the time. He was a Republican, a member of the Republican Party, but his ideology was very libertarian, very shaped by Mises and Hayek and Rothbard and Leonard Read and FEE. So, he was this real weird outlier, this Texas congressman known as “Dr. No,” because he was always the one guy who would vote no against unconstitutional legislation. And he only gets about three pages in my book, right? Because that was about as big a figure in the political culture as I saw him to be when I was finishing the book up in 2006. But something happened in 2008 and then again in 2012, and I wrote another whole book about that called Ron Paul’s Revolution, which is that this guy, an absolute child of the American libertarian movement, as I had written the book about it, decided to run for president, this time as a Republican. He had actually run with the Libertarian Party back in 1988, which of course, like with most third party runs, got very little attention, but he decided to contest the Republican primary in 2008, and he achieved things that blew my mind. I was covering his campaign, so I would go to college campuses in California and Iowa and New Hampshire, and I would see this guy selling like straight-up Rothbardian radical libertarianism, gathering thousands of college kids who were just cheering him on, cheering on the most bold and uncompromising statements about liberty and not in a culturally conservative context either.

This is a complicated question with Ron Paul because Ron Paul himself is pretty culturally conservative, and if you look at what’s happened to the Ron Paul movement in the last decade, I think it’s fair to say that a strain of cultural conservatism has gone through that movement. But the Ron Paul who ran for President in 2008 and 2012 was just a pure bore, straight up libertarian message of liberty for all, and it resonated, and he did amazingly well. Obviously he didn’t win, but he got delegates, he got dozens in 2012. He fought it out to the end. I thought at the time that he was going to change the Republican Party for the better in the future. I think that didn’t quite come true in the Trump era. This might not be the time or place to litigate the meaning of Trump, though I want to say a couple of things about it.

Movements have emotional importance as well. Just having other people who let you know you’re not crazy.

So, what Ron Paul did, I think, the mass movement he created for no government-managed currency, for a foreign policy of complete peace, for an end to the welfare state, an end to the warfare state, it blew my mind how well he did with that message. I mean, obviously it didn’t take over the world. It didn’t even take over the Republican Party, but it was proof to me that the work that Leonard Read did, that Mises did, that Rothbard did definitely was going to have a future. And in the internet era, the spread of these ideas is so easy. You know, when I was a kid, you had to get this weird little secret catalog that I mentioned earlier and mail things in and then you’d get a book. But nowadays it’s all out there on the internet.

And the fellowship is out there. I alluded to the importance of movements. Movements have emotional importance as well, not just like, there’s an organization to give you a job or there’s a foundation to give you money for your project. Just fellowship is important. Just having other people who let you know you’re not crazy. Your parents might think you’re crazy, your college roommates might think you’re crazy, your wife or husband might think you’re crazy, but you’re not crazy. These ideas are great, and these ideas are going to win. The internet has been great for creating that sense of community. So, in terms of the livelihood of the ideas, 100% great. Obviously the question then becomes, “If you libertarians are doing so well, why aren’t you winning?” Well, we’re not winning for all the same reasons we’ve never been winning. I feel like I’m talking to the choir here. The federal government and state governments have just taken upon themselves such an enormous place in everyone’s lives and running this program and that program. It’s hard for anyone to imagine how the world could run without them. You know the famous phrase that we economically minded libertarians will always say: the issue of concentrated benefits versus diffuse costs, which means the government gives a lot to a lot of people and it takes a little from everyone. And so the people who are getting what looks like a lot are like, “We’re going to fight for our program. You’re not going to cut the healthcare, you’re not going to cut this, you’re not going to cut that tariff, you’re not going to cut anything because I’m benefiting a lot from it and I’m going to vote you out of office if you don’t give it to me.”

I know this is highly arguable—I’m not sure where you guys stand, and I don’t know if there’s any point in fighting about it—but I think while Trump himself wasn’t a particularly libertarian figure, Trumpism has this one real strong positive thing for libertarians. It really has spread a widespread sense of contempt, both for his fans and for his enemies, for government. The sacredness of government has, I think, been dinged in a really strong way by Trump, again, both for the people who love Trump—because Trump is like this rampaging id who just says what he thinks and he doesn’t care about the pieties of this or that, he’s really telling it like it is—and if you hate Trump, you could go, “Huh, do I really like the idea of a federal government with all these powers, if a guy like Donald Trump is going to get to run it?”

So I think that the echoes in the culture of Trump have the potential to be positive for libertarianism. They have the potential to go the wrong way, too. They have the potential to have a sort of Kamala Harris, full-on communist backlash, or they could have a sort of proto-fascist, “We’re going to close the borders and shut off the world economy and be very mad at anyone who’s not like us.” It could be a bad thing too. But I think the libertarian ideas are out there, and I think it’s better for the libertarian, both intellectually and spiritually, if I may say so, to be optimistic and know that the best that we can do as libertarians, libertarian intellectuals, activists, fans of libertarianism, is just keep the ideas alive, explain them, write books and magazine articles about them, podcast about them, tweet about them. Just let people know in a time of chaos and upheaval that freedom is an option, and it probably could be a pretty good one. So that’s my big picture on that.

Roger Bissell

Well, you’ve really answered my next question very well. That really encapsulates a lot of the concern that I’ve been having. Like, is there still time to save America from tyranny and what should we do? Well, yes, we keep the alternative alive. Make sure people know. Marco, now I think is a good time for your next question.

Marco den Ouden

Yes, thank you. Brian, in a recent book by Walter Block and Alan Futterman, they write that, quote, “The entire libertarian movement is the outcome of the efforts of one man in particular, Murray N. Rothbard. Rothbard was the virtual founder of the theory of anarcho-capitalism, an application of free market economics to government functions. Not only did he expand economic theory, focusing on free markets, he practically created the entire philosophy of libertarianism.” Of course, there are other views. Your book goes back into history looking at Jefferson, Locke, and other influences in the libertarian movement. If there is a single seminal thinker who embodies the essence of the libertarian movement, who would you say that is?

Brian Doherty

Rothbard is a very good answer to that question. I’m going to nuance it a little bit and explain. If people listening aren’t that familiar with Rothbard, I’ll give you a little background as to why I say that. Now, I have to preface this with, of course, Rothbard had intellectual influences before him. I’d say the most important ones were Ludwig von Mises for his vision of economics—and Rothbard was professionally a professor of economics, and he wrote some amazingly good books about economics—and Ayn Rand; though Rothbard feuded with her later in his early days, he was very influenced by Ayn Rand.

There was a time in the late ’60s when the entire libertarian movement could fit in Murray Rothbard’s living room.

But the thing that Rothbard did, and this gets back to what I was saying earlier about the importance of not just libertarian ideas, not just libertarian books, but a libertarian movement, is Rothbard was the guy who most strongly actuated that idea, the idea that you needed to bring people together, and you needed to create and support institutions that would push libertarian ideas, nearly every institution that anyone has heard about pushing libertarianism from the ’50s on. He wasn’t around early enough to be there at the founding of FEE, but he was working with FEE very early, by the end of the ’40s he was working with FEE. The Institute for Humane Studies, he was very core in the founding of that. There was an organization called the Volker Fund in the ’50s; in helping support them, Rothbard was one of the driving forces behind that, helping them vet and find and support libertarian thinkers. The Cato Institute, he was there at the founding of that. He was not a founder of the Libertarian Party, but he was involved in it very early and for a long time.

You’ll hear a phrase, and there’s some truth to it, that there was a time in the late ’60s when the entire libertarian movement could fit in Murray Rothbard’s living room. There was some truth to that, but the important aspect of that was that he was gathering people in his living room, and he was getting them to see each other as friends and colleagues and people together in this world-shaking mission to bring these great ideas of libertarianism to the world. And if you live in the online world of libertarianism, I think you will find that Murray Rothbard, even more than Ayn Rand, certainly more than Mises, if you’re a young firebrand tweeting about libertarianism, Rothbard’s your guy. The people who came through the Ron Paul movement, most of them are fans of Rothbard more than they’re fans of any of the others.

One of the things that’s important about that, and you mentioned this earlier, Rothbard pushed a line of thinking that’s often called anarcho-capitalism. Now, not every libertarian is an anarchist. There are some people who call themselves libertarians who have more of an American Founding vision of a government strictly and constitutionally restricted to the protection of our rights and to securing our liberty into running a justice system, into running defense, right? I happily accept people like that within the libertarian movement. But there’s a lot of libertarians inspired by Rothbard who don’t think there’s any need for any government at all, who think that the free market and private institutions can provide everything a human society needs. If anyone is hearing this idea for the very first time, obviously it’s not going to sound convincing in a podcast; but if it intrigues you at all, or if you even want to go, “Huh, how could anyone believe such a crazy thing?” I advise you, I’m going to say read my book, Radicals for Capitalism, because I explain in context. Or, if you want to go directly to the source, look up Murray Rothbard online—Murray Rothbard, anarcho-capitalism—and you’ll find out. And that idea, that really mind-blowing idea that maybe we don’t need a state at all, I have found in my years in the movement, it excites people, right? Because it’s so mind blowing. A lot of people are very attracted to an idea, the wilder it is, and a lot of libertarians, as I’m sure you guys know, tend to have wild personalities in some way or another.

Rothbard was key to building most of the major libertarian institutions.

So, to sum up, Rothbard was key to building most of the major libertarian institutions. He was key to this idea of anarcho-capitalism that is unique to the American libertarian movement. He was one of the great explainers of the Misesian-Austrian tradition in economics, which is the dominant but not only economic tradition within libertarianism. There’s also Milton Friedman, the Chicago School. It’s all very complicated. That’s why I wrote a 700-page book. But yes, the capstone is in the post-Ron Paul era. If a young libertarian has a favorite libertarian thinker, it’s very likely to be Murray Rothbard—or if not Murray Rothbard, the student of Rothbard’s who I will just say I’m not a very big fan of. We don’t need to get into it, but it would not be fair not to mention him, a guy named Hans Hermann Hoppe. So yes, Rothbard is absolutely central to all of this. And I would certainly not get in a fight with anyone like Walter Block who says that the movement can all be laid at his feet. So, you do have to remember that his intellectual evolution has to be laid at the feet of your Mises and your Rand. That’s what I have to say about Rothbard today.

Roger Bissell

Excellent. This is a bad joke, but I would say if Murray Rothbard is wild, then Laura Ingalls is wilder. I would just add to your recommendation about Rothbard and also Hoppe and other people, the Mises Institute, which you can easily find online. The Mises Institute has an enormous amount of material that you can download absolutely free as PDFs. You can get essays, sometimes you can get the books, you can learn to your heart’s content. Also, your own book is an excellent guide and overview. I was going to point our attention more now to the present time, the present generation of the intellectuals. I know back, years ago, the two main factions were the anarcho-capitalists and the limited governmentists. Now it seems that there is a different kind of parting of ways or at least different emphasis. There are some libertarians who are more in favor of what they call social justice, or they call themselves bleeding heart libertarians; and then there are some who are more culturally conservative instead of culturally liberal and they are I guess you might call them paleo libertarians. I think some of the people affiliated with the Mises Institute are more in that direction; and if you have some thoughts on those two strands of libertarian thought, I’d like to hear what you have to say.

Brian Doherty

You bet. I’m actually going to throw out, for people who are in front of their computers, that there’s an essay I wrote to this point, and I’ll try to sum it up without reading an entire essay to you guys now. If you search my name, Brian Doherty, the title of the essay is “A Tale of Two Libertarianisms,” you will find more thoughts on this. In that essay, I use Rothbard, as we’ve just been saying, as the leader of the paleos, as you just aptly describe them, and Hayek as the leading light of the more bleeding—and Hayek would never have used this phrase himself, but, you know, a lot of Hayekians adapted that phrase in the 21st century, as you mentioned. So, again, one of the big differences is that Rothbard and the paleos in the Ayn Rand tradition have a strong belief in what they consider inalienable natural rights, right? I mean, some people might look at free market economics and go, “Okay, so free market economics tells us that in most cases, private property and the free exchange of it seems to lead to the most wealth, and it seems to do the best for a lot of people.” But bringing in the philosophy of the great modern liberal philosopher, John Rawls, John Rawls was like, “Oh, but we really need to shape the society so that the least worst”—so how does he put it? He has a weird way of putting it, but the idea is: whereas a libertarian would say we need to shape a society so that people’s right to their life and property is not interfered with, that’s a libertarian, Rothbardian, paleo outlook, the Rawlsian outlook, which many bleeding-heart libertarians embrace, is that we need to shape a society so that the least well-off are doing the best they can, right?

I don’t know if I’m explaining this right, but they believe that, hey, we all agree that free markets mostly create a really rich culture, a rich society. We’ve seen this over the course of the 20th century. We’ve seen communism and centrally planned economies be poor and miserable and tyrannical. And we’ve seen the West, which obviously is not a libertarian paradise, but has more free play for private property, more free play for free exchange, more respect for individuals’ rights in the courts or whatever, that’s the rich part of the world. And so even if the sort of bleeding-heart libertarians—and they actually use a very awkward phrase, Rawlsekian, which is the mixture of Rawls’s belief in shaping society so the least well-off are doing the best they can, and Hayek’s belief that free markets are the path to that—mostly believe in free markets, they don’t have the sort of moral passion about the right to be unmolested in your person and property that the Rothbardian has. If you’re looking at it in that pragmatic way, you might go, “Yeah, free markets are mostly okay, but surely we need some sort of government safety net,” which Hayek did believe, “and we need some sort of government provision of certain social services, and we need the government to make sure that there aren’t externalities from your use of private property that hurt other people.”

To a Rothbardian, to a paleo, it’s just not hardcore, it’s not a very philosophical term, it’s not sharp enough, it doesn’t get you to where the libertarian wants to go, it’s too squishy. It allows too much room for the state to do too much. And the Rothbardian, the paleo, tends to be “The state is positively evil.” You’ll find a lot of very moral language. “The state is the institution of warfare. The state is the institution that destroys human lives over private personal choices they make, it destroys human lives over whether they’re zoned properly to build the thing they want to build on their own property. The Rothbardians, the paleos, view the state as evil; and the bleeding heart—I’m generalizing here, of course, but I think there’s a lot of truth to it—is more apt to just go, “Well, yeah, the state is inefficient, and the state doesn’t always do what the state should do, but they mean well, and it doesn’t help to approach non-libertarians with this sort of moral dudgeon of, “You’re evil, and you’re the worst thing that ever lived, and you should be locked up in Guantanamo Bay,” or whatever. That kind of attitude you’ll find more prevalent in the Rothbardians.

There is no one approach to selling libertarian ideas that is going to convince everyone.

I feel like maybe—I don’t know if I’m getting a little afield of this or there’s a way for me to pin this down a little more—the bleeding heart is more apt to be comfortable in a normal academic institution. They’re more apt to be comfortable in D.C. They’re more apt to be comfortable talking to some liberal at the Washington Post, whereas the Rothbardian paleo is more like, “No, we’re just creating our own institutions over here, and we’re right, and our ideas are correct, and these guys are all evil idiots, and we don’t want their respect, and we don’t need their respect, and rather than win them over, we’re going to push the idea of secession, national divorce, we’re just going to take over the state of New Hampshire, and screw the rest of y’all.” So there’s kind of a difference, both in philosophical basis, there’s a difference in how far you take your anti-government attitude, there’s a difference in how you approach the standard bastions of culture, there’s a difference in just how pugnacious you are.

I hope I’ve gotten that across pretty well. I myself, I want to say as the person who wrote this book, I came to the belief that there is no one approach to selling libertarian ideas that is going to convince everyone. So you might be a mild-mannered professor at some state university who finds Rothbard and Rothbardians a little “They’re going a little too far,” or whatever; or you may be an angry 22-year-old Rothbardian on the internet who thinks Milton Friedman is a horrible sellout, right? I think all of those people and everyone in between has a very vital role to play in the libertarian movement because their way of selling the ideas and pushing the ideas is going to appeal to someone, and none of them are going to appeal to everyone. It’s the same lesson we learned from free markets: there is no one business, no one product that’s going to appeal to everyone. The glory of free markets is that it allows—that horrible Maoist cliche, but it’s appropriate—the thousand flowers to bloom, that’s going to satisfy everyone. So, I think as someone who wants to see libertarian ideas win, I don’t want to make myself an enemy or attack any of these sides. I think they all have something important to say to someone whether or not I agree with them all or not. So, I’m kind of squishily ecumenical, and every libertarian is A-OK. I hope that gets to what you’re asking.

Roger Bissell

I appreciate that very much. I’m a semi-retired trombone player in smalltown Tennessee, so I don’t know where I fall in all that. Maybe through the cracks is where I fall. I won’t say a plague on both their houses, but maybe a mild sniffle, alright? I think we’re up against our time here. This is very stimulating, very interesting. You have an awful lot to share with us, and I want to thank you, Brian, very much for being here with us and also you, my cohost Marco, thanks very much for helping out. In the words of our regular host, Vinay Kolhatkar, I wish both of you and our audience good night and good luck.

Related Posts:

About the Author: The Savvy Street Show

-

Book Review: Modernizing Aristotle’s Ethics

May 7, 2024

-

Transcript: Brian Doherty Interviewed on The Savvy Street Show

April 28, 2024

-

Retaking College Hill Proved Startlingly Prophetic

April 27, 2024

-

Libertarian Party Candidate Vinay Kolhatkar Cook Campaign Video

April 24, 2024

-

Brian Doherty on The Savvy Street Show

April 24, 2024

-

What Does a Political Campaign of Speaking Truth to Power Tell...

April 24, 2024

-

China Now Sets the World Gold Price—Preparing for A Gold-Backed Currency

April 21, 2024

-

Transcript: Ayn Rand and the Austrian Economists

April 16, 2024

-

After the Founding: The Demise of Laissez Faire in America

April 6, 2024

-

Doubt and Certainty

March 26, 2024